Factsheet Five: The Zine of Crosscurrents and Crosspollination

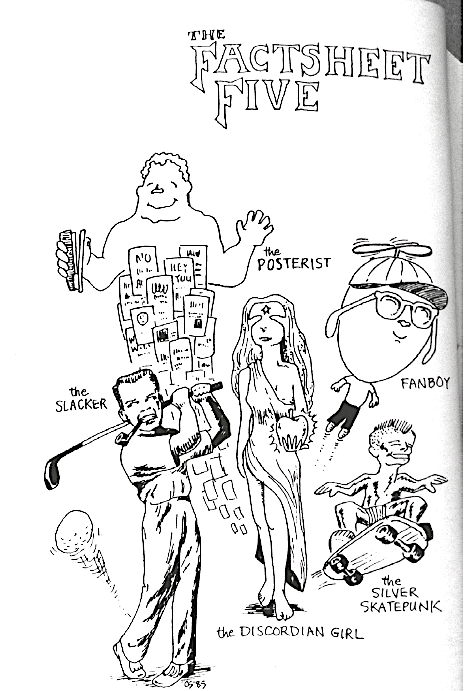

The above image appeared as the back cover of issue fourteen of Factsheet Five, published in 1985. Entitled “The Factsheet Five,” the image is a parody of the Marvel comics’ superhero team known as “The Fantastic Four”. In lieu of superheroes, the image portrays personifications of the five most prevalent topics featured in the pages of Gunderloy’s zine. These include representations of the SubGenius deity “Bob” (“the Slacker”), the Discordian goddess Eris (“The Discordian Girl”), a science fiction fan (“Fanboy”), a punk (“the Silver Skatepunk”), and a pro-Situ posterist.)

The zine scene of the 1980s and 90s was a tangle of overlapping communities. Scores of tributaries fed into this underground ocean of non-commercial, self-published material, and their convergence produced a highly eclectic intellectual culture. As one commentator noted, the zine scene was comprised of “a nebulous weave of pen pals and computer enthusiasts, Whole-Earthnostalgists, futurologists, anarchists, food cranks, neopagans and cultists, self-publishing punk poets, armchair schizophrenics, survivalists and mail artists.” Ken Thomas, a zine editor with a special interest in conspiracy theory, described the zine scene as “populated by small presses devoted to a wide variety of subcultures and specialty interests, including Satanism, erotics, Reichian orgones, Marxism, the Situationists, the anarchists and the nihilists as well as ufology and conspiracy.”

The most ethnographically satisfying index of this literary republic, though, appeared on the back cover of Semiotext(e) USA (1987). The principal mass market anthology of zine writings described the citizenry of this bohemia as “anarchists, unidentified flying Leftists, neo-pagans, secessionists, the lunatic fringe of survivalism, cults, foreign agents, madbombers, ban-the-bombers, nudists, monarchists, children’s liberationists, tax resisters,zero-workers[.]” The list went on to include, “mimeo poets, vampires, feuilletonists, Xerox pirates, prisoners, pataphysicans, unrepentant faggots, witches, hardcore youth,poetic terrorists.” Yet, for all of their apparent difference, these subcultures formed an organic intellectual community bound together by an ethos of communitarianism (and, in many cases, hatred of the status quo).

This literary domain was not locked into what economists term “rivalrous competition.” Unlike the world of commercial publishing, the zine scene was a fundamentally collaborative. To be certain, zines were, first and foremost, participatory: readers often contributed to zines, if they were not editors themselves. A fundamentally variegated medium, zines promoted category confusion by celebrating intellectual hybridity, bricolage, and synthesis as self-evident virtues. Participants were most often of certain movements (through the use of their symbols, logics, etc.), but not unequivocally in them. This is especially true of the SubGenius movement, whose symbols became the de facto icons of the zine scene. The immense complexity of the zine network became clear to me during my research trips to the Factsheet Five archive housed at the Albany branch of the New York Public Library.

At first, making sense of this archive seemed impossible due to the tendency among zine editors to discontinue their publication after one issue, unexpectedly change the title of their zine (e.g. Joel Biroco’s seminal chaos magick zine Chaos became Kaos mid-way through its publication run), and purposefully mis-date their publications. This is to say nothing of the highly erratic publishing schedules by which zines were printed. Moreover, the population of thezine scene was in a constant state of flux, as new participants entered and others constantlydropped out. Add to this the custom for contributors to employ numerous pseudonyms,and it became clear to me that this imaginal bohemia operated by rules entirely its own.

Having read zines for a few years myself, though, I did have a basic heading to begin with. Mike Gunderloy’s Factsheet Five served as the primary meeting-grounds for the dispersed community of zine makers. Gunderloy’s zine installed the modicum of centralization necessary for the zine scene to flourish across the 1980s and 90s. Here, I would like to clarify the particular relationship between Factsheet Five and the Church of the SubGenius, the foremost psychedelic church of the post-1960s. Produced by members of the SubGenius movement, The Stark Fist of Removal exerted a gravitational force within the 1980s underground thereby accelerating the cross-pollination of the otherwise insular zine micro-communities that had coalesced since the mid-1970s. Freethinking punks, anarchists, occultists, and science fiction writers – amongst a host of other hip dissidents – congregated under the auspices of this psychedelicist church to share ideas, hatch schemes, and exchange polemics. Responding to the surge of enthusiasm stirred by the SubGenius Church, Mike Gunderloy published his zine, Factsheet Five, which did not feature articles, like The Stark Fist; rather, it was a directory of addresses for the “superior mutants” congregating by the hundreds within the Church of the SubGenius.

Gunderloy’s zine became immensely influential on account of its practical utility. Factsheet Five allowed zine readers to kept up-to-date within their underground, and decentralized print microcosm. Given the self-consciously anarchic nature of

zine scene culture, it would be inaccurate to characterize Gunderloy as a hierarch of any sort; however, as the creator of Factsheet Five, he was in a privileged position with respect to the other networkers that inhabited this epistolary bohemia. Accordingly, it must suffice to say that Gunderloy was first among equals within the zine milieu.

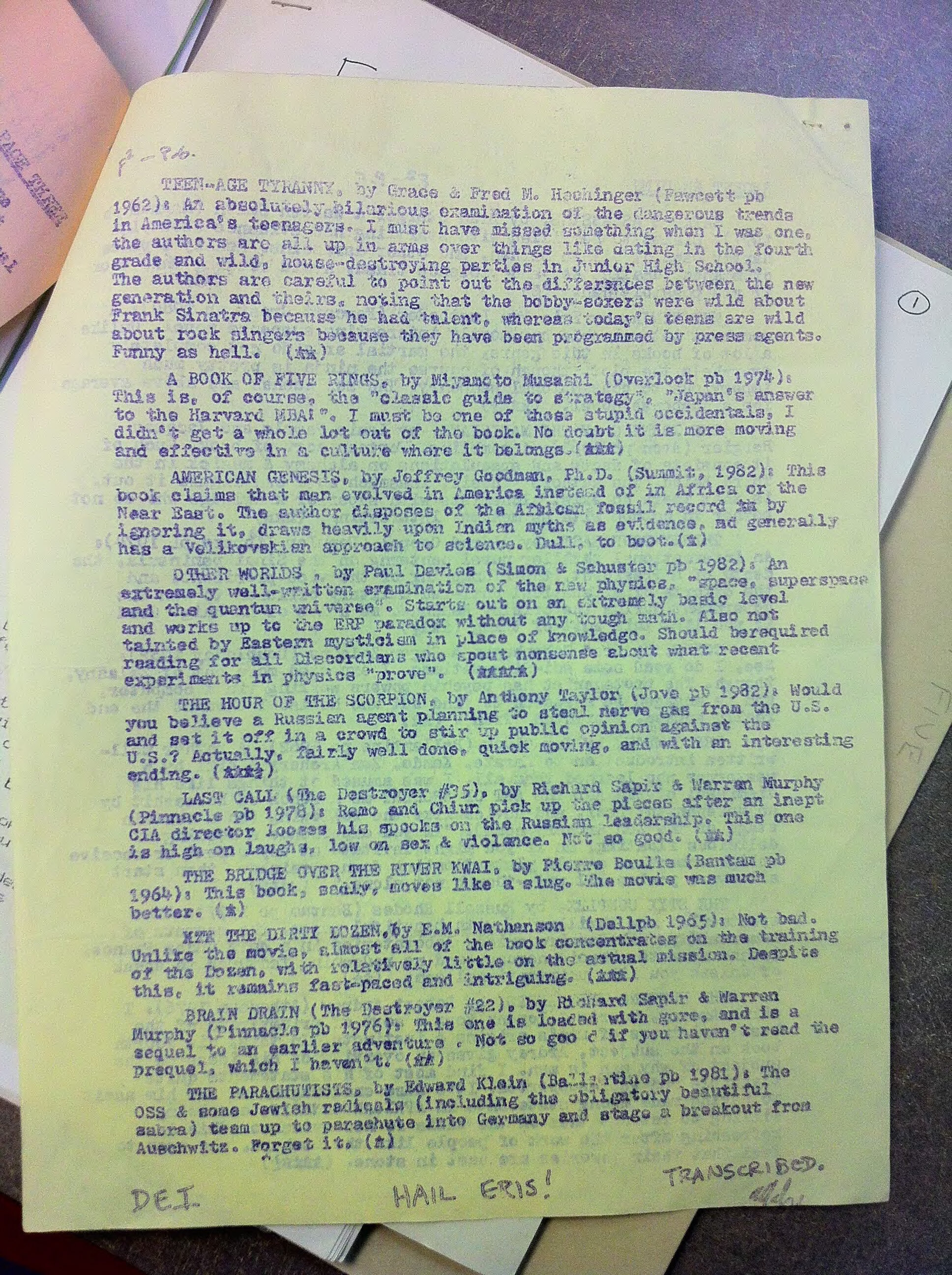

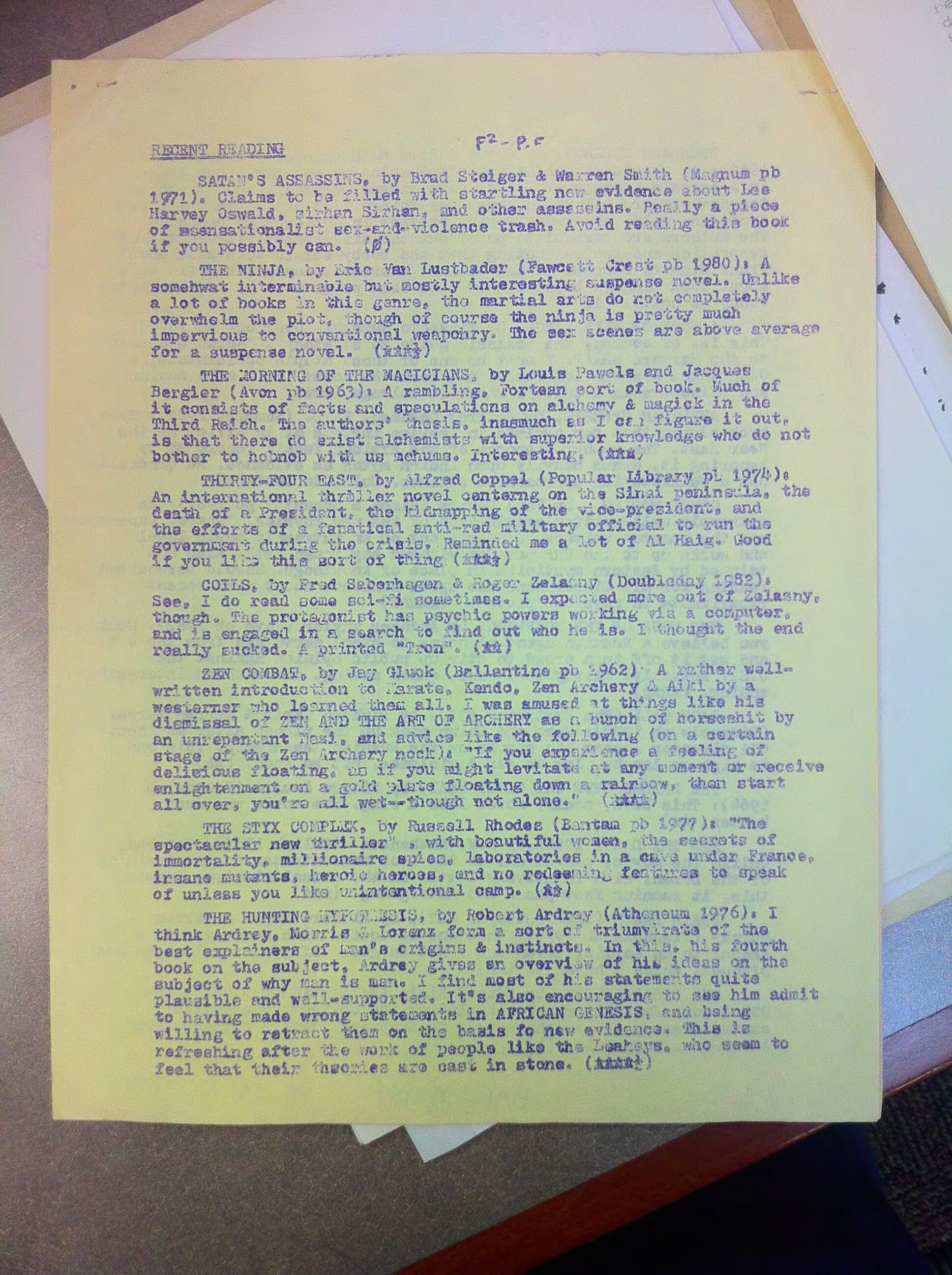

Below readers will find the earliest issues of Factsheet Five. Apologies are in order, as the photographs presented below were made in haste, and are therefore low-quality and, in some cases, blurry. These images were necessary for my dissertation research, and, at the time they were captured, I did not have the foresight to reckon others would be interested in them. Needless to say, I am overjoyed you are here, and welcome any reflections you may have about Factsheet Five, the flagship publication for the wonderful world of fanzines.

Factsheet Five no. 1

Factsheet Five no. 2

Factsheet Five no. 3

Factsheet Five no. 4

Factsheet Five no. 5 [MISSING]

Factsheet Five no. 6