History of the Moorish Othodox Radio Crusade

Introduction

Bill Weinberg knew that someone would eventually come asking about the cassette tapes deteriorating in the back of his closet. At least, that was the impression I had when, after a careful vetting process conducted through a mutual acquaintance, we first met in his Lower Manhattan apartment. I will spare the reader a full account of my hunt for recordings of The Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade (henceforth MORC), a radio program that aired live every other Monday night, from 1am to 2am, on New York City’s non-commercial, listener-sponsored public radio station, WBAI. Though it was broadcast for thirty-six years (1987-2011), at no point did the station archive its episodes. After a few years of following dead-leads, I had concluded that MORC was lost in the radiophonic ether of live broadcasting. Then I met Bill (fig.1).

Fig. 1: In addition to hosting MORC for over a decade, Bill Weinberg also served as the show's ad hoc archivist. If it were not for his preservation efforts, there would be no MORC archive.

Having co-hosted the show for the last nineteen years of its run, Bill appreciated my fascination with MORC. Like him, I recognized this radio program as a landmark in the “rebel culture” (to use Bill’s words) indigenous to New York City. Indeed, on that damp June night when I first surveyed his archive, I felt as though the Akashic records lay before me. Like this archive of mystical lore, which fascinated turn-of-the-century Theosophists before reappearing in the Doctor Strange comics of the 1960s and 70s, the towering stacks of decaying cassettes my host produced from his bedroom closet offered to disclose a lost world of esoteric knowledge. In less fanciful terms, Bill’s cache was a treasure-trove of raw -or rather unexamined- documentation of spiritual rebellion in the age of psychedelics.

Certainly, it is possible to historicize the mythopoetic story of psychedelic militancy in the US without the MORC archive. Since the mid 1980s, there has been a steady flow of books, written mainly by sympathetic journalists, which have accomplished this task rather adeptly (Lee & Shlain, 1985; Stevens, 1987; Jarnow, 2016). As I see it, the MORC archive adds another layer, or “sub-plot” if you will, to the conventional narrative of the psychedelic uprisings of the 1960s. This sub-plot concerns the role of the acid fellowships, brotherhoods, and churches that not only evangelized the good news of LSD, but risked their freedom by distributing the “high sacrament” to their brothers and sisters. Though scholars have recognized the integral role these churches played in the urban psychedelic enclaves of the 1960s, there has been no systematic study of their beliefs and practices (Miller, 1991: 32-34). Considerably less attention has been paid to the history of this outlaw church phenomenon in the decades leading up to the millennium. The MORC archive sheds considerable light on this underground tradition, as it was the product of one such fellowship, the Moorish Orthodox Church of America (MOCA). By historicizing its broadcast history, it is my hope to illuminate, however partially, the continued vitality of this psychedelic militancy.

The MOCA first emerged as a minor spiritual force in the Upper West Side of Manhattan during the mid-1960s. Though private, the church was not secret, and members operated their own temple (nicknamed “The Crypt”), which simultaneously served as a head-shop, reading room, and clubhouse for their motorcycle gang (“The MOCMC”). Moreover, it produced its own photo-offset publication, The Moorish Science Monitor, and broadcast, albeit irregularly, its own radio program on WBAI from 1964-1967. If reel-to-reel recordings of this initial iteration of the Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade exist, they have eluded me. Nonetheless, twenty years after the original MORC went off the air, a member of the church, Peter Lamborn Wilson, revived the show and consequentially ushered in a revival of Moorish psychedelicism among radicals in the late 1980s.

This essay will examine the legacy of militant radio psychedelicism by taking a closer look at the revived MORC program. The “radio sermonettes” produced by Wilson, Weinberg, and the rest of the MORC collective embodied a tradition of broadcast activism that had been established decades before (Wilson, 1991). To be precise, the after-midnight timeslot on WBAI that MORC occupied was consecrated as hallowed ground, radiophonically speaking, in the early 1960s by the legendary Yippie broadcaster Bob Fass. His program, Radio Unnamable (1963-1977), transcended mere entertainment and became a nexus for the utopian uprising, or “revolution in consciousness” materializing in the bohemian colony on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In what follows, I will demonstrate how Wilson and his crew of spiritual rebels adapted the psychedelicist style of radio broadcasting that Fass pioneered on his own show decades previous.

Bob Fass’ Radio Unnamable

Fig. 2: Host of Radio Unnameable, Bob Fass, participating in the "Sweep-in" that cleaned -up the mountain of garbage that accumulated along 7th Street in Manhattan. The Diggers conceived of the idea and Fass used his show to orchestrate its execution on April 8, 1967. His show was also integral in organizing the Fly-in (Feb. 1967) , Central Park Be-in (April 1967), and Yip-in (March 68).

The latter-day iteration of MORC participated in a tradition of broadcast radicalism that originated during the so-called ‘hippie era’ of the 1960s. Beamed out live across the airwaves from midnight until 5am, Radio Unnamable began just as all of the other radio programs were signing off for the night. Addressing itself to the rare state of ferment then percolating in Lower East Side, Fass’ show was the radiophonic hub for the nascent colony of beatniks, hustlers, and juvenile runaways congregating within the nocturnal metropolis. As the lone voice on the radio dial, Fass took to the air just as this heterodox community came to life. Embedded in this budding enclave, Radio Unnamable nurtured a growing sense of radical communitas that would become mainstream news following the “Summer of Love” in 1967.

Radio Unnamable was “unnamable” because it broke with the conventions that governed broadcast programming. As host, Fass (fig.2) refined a style of free-from broadcasting introduced not long before by Jean Shepherd, an exciting, though patently more staid radio personality. Evoking the expansion of consciousness spurred by LSD (Fisher, 2007: 132), Fass’ stream-of-conscious oration went beyond bop prosody monologues, to include freewheeling, multi-caller discussions that transgressed the well-defined boundary that separated broadcaster and listener. In his history of alternative radio, Jesse Walker argued that “[n]o show had ever been so participatory” (Walker, 2001: 74), though it bears mention that the call-in format of Radio Unnamable was inspired by the Fortean broadcasts of Long John Nebel. Influences aside, Fass’ show was akin to an on-air conference room in which the New York bohemian colony hashed out its values, beliefs, and utopian visions for a new society.

Radio Unnamable showcased the ideas and ideologues that characterized the lysergic culture as it was taking shape on the East coast. Turning-on and tuning-in on any given night, listeners could catch energized discussions with the reigning LSD patriarchs of the era, including Timothy Leary, Allen Ginsberg, or Wavy Gravy; or perhaps they would hear a live jam session by one of the popular protest balladeers such as Bob Dylan or Pete Seeger. Acting as a sort of talking drum for the bohemian colony in the East Village in particular, the show also featured more “far-out” artists from the East whose music would not have been available on any other stations. For all of its significance as an underground media showcase, though, Radio Unnamable played a much more substantive role in orchestrating the utopian excitement that was taking place across the North East.

Until the Summer of Love brought droves of seekers to San Francisco, Manhattan was one of the epicenters for psychedelic culture. Without discounting New York’s own indigenous bohemian culture, the centrality of the Lower East Side was due, in large part, to its proximity to the Millbrook estate, the Vatican of lysergic religiosity (Paglia, 2003: 63). Located less than two hours up-state, this lavish piece of real estate (including a mansion, bowling alley, private gardens, etc.) was generously donated to the “high-priest” of acid, Timothy Leary, by the heirs of the Hitchcock-Mellon fortune. Leary, along with his band of defrocked Harvard colleagues, transformed the estate into a vibrant center of religious and social experimentation that attracted thousands of psychedelic pilgrims for the duration of his existence (1963-1968). In addition to being the seat of Leary’s church, The League of Spiritual Discovery, the estate was also home to other psychedelic sects, including Art Kleps Neo-American Church, and the Sri Ram Ashram led by Swami Bill Haines. The combined energy of these churches generated a great deal of enthusiasm that flowed directly into Manhattan’s psychedelic scene.

Fig. 3: The Central-Park be-in of 1967 was the first of many "tribal gatherings" in which the psychedelic spirit of universal brotherhood was celebrated out in the open by 10,000s of people.

Historians refer to Radio Unnamable as the “mid-wife to the movement” due to its formative role in the coalescence of the East village psychedelic scene (Cottrell & Browne, 2018: 13). This scene included numerous militant groups whose diffuse activities collectively created an atmosphere, or social envelope within which a vibrant utopian community took shape. Fass’s show, then, was imbricated with the work of militants, like the Diggers, Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers, and The Living Theatre, which collectively shaped the culture of psychedelic militancy on the East Coast. This culture was organized around a variety of social project, including the Diggers’ “Free Store,” as well as the network of crash-pads set up to accommodate the steady stream of psychedelic seekers that flowed into the city. Similarly, Kerista, a local, psychedelic free love sect founded in the mid-1950s, supported the community by coordinating communal meals and orgies on a regular basis. Imbued with the spirit of these utopian projects, Fass’s program served as the staging area for the fantastic events that were crucial in forging the sense of shared identity that distinguished the denizens of the Lower East Side from citizens of the “straight world”. Most famously, Radio Unnamable introduced the principle form of psychedelic activism to the East Coast: the be-in. As we shall see, the organization of these bold demonstrations of love was to become a hallmark of militant radio psychedelicism.

The original Human Be-In, staged in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park on January 14th 1967, was modeled on the sit-in technique of non-violence formerly employed by the Civil Rights protesters in the 1950s. Instead of confrontation, though, the be-in technique was deployed as a means of exhibiting the power of love in the here and now. In the words of the Living Theatre, it represented “Utopia Now”. In the months following its deployment on the West coast, this utopian technique was transposed to the New York City through a series of coordinated by Radio Unnamable. The number of be-ins in 1967 alone is impressive: among the most memorable were the Sweep-In (to beautify the refuse-laden Lower East Side), the Central Park Easter Be-In (fig.3) and satirical Fat-In, the Fly-In at JFK airport, the Giant Moon-In in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, the open-air cannabis Smoke-In, and the inaugural Flower Power Rally on Armistice Day that took place in Mid-town Manhattan (Harder, 1968: 60; Grogan, 1972: 332-334). Though clearly a partisan of psychedelicist militancy, Fass also lent support to New Left/anti-war activists, who came to rely on Radio Unnamable to get the word out about their more conventional protests. By bridging the psychedelicist utopian agenda and the New Left culture of protest, Radio Unnamable became a nexus for the mounting sense of revolutionary fervor that was flaring up across the greater New York metropolis. According to Marc Fisher, “[b]y the end of 1967, Fass’s listeners were a street force” (Fisher, 2009:143). His depiction of the cultural crusade of Radio Unnamable as a “force” is essential to understanding the legacy of radio psychedelicism. MORC proved itself to be the successor of Radio Unnamable by continuing to cultivate this militant force, as demonstrated in the next section.

One final point regarding Fass’ broadcast crusade merits note. Radio Unnamable was the media organ for the Youth International Party (YIP!), a vanguardist psychedelicist group established on New Year’s Eve 1967. Formed in Manhattan, this group of self-styled “psychedelic Bolsheviks” formally announced its incorporation live on Radio Unnamable (Ibid, 2009:144). Fass was a member of its inner circle, alongside other militant “heads” such as Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, Paul Krassner, and Ed Sanders. According to Hoffman, Fass’s show was “the secret weapon” in the Yippies’ arsenal insofar as their immediate aim was the creation of a counter-myth, pace George Sorel, that would replace the stereotype of the lumpen hippie with the image of militant psychedelicist, or Yippie (Raskin, 1997: 129).

YIP! fortified their media campaign with an activist platform that overcame the decaying rationalism of the New Left. Instead of political reforms, these modern antinomians insisted on the total abolition of industrial Western society and the birth of a new, theocentric, or rather psychedelic way of life (Urgo, 1987: 83-84; Hoffman, 1968; Rubin, 1970). The Yippies’ program typified what the historian James Webb referred to as “illuminated politics” insofar as their agenda transcended political reform and instead sought to overthrow the entire technocratic social order so as to usher in a renewal of the human spirit. In short, their aim was the re-enchantment of everyday life (Wilson, 1998: 66). Though never systematized, the Yippies’ program of psychedelic militancy was cogently summarized by John Sinclair, the Chairman of the White Panther Party, as “the total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock and roll, dope, and fucking in the streets” (Sinclair, 1972). Specifically, YIP! orchestrated media hoaxes, street-theatre, and bold demonstrations of love that were designed to effect a permanent change of heart in their opponents. Altogether, their unconventional tactics epitomized Flower Power, a slogan coined in honor of Black Power, the rallying cry for the Black Panther Party. Instead of conquering their foes, this politically assertive mode of psychedelicism focused on converting them by “blowing their minds” into a higher order of awareness. The original, militant meaning of Flower Power had long been forgotten by the time Peter Lamborn Wilson revived the MORC in the mid-1980s; nonetheless, this style of illuminated politics was at the core of his show.

James Irsay’s Primary Sources

The tradition of militant radio psychedelicism continued after WBAI management removed Bob Fass from the air (following a protracted dispute) in 1977. When the dust settled, his midnight slots were then handed over to another broadcaster, James Irsay (fig.4), whose popular piano music show aired during the day. In lieu of imitating his legendary predecessor, Irsay created a wholly new show, Primary Sources, which explored ancient religious heterodoxy through close readings of extant source material. Striking a balance between reverence and levity, the host approached the ambiguities and incongruities of the pseudepigraphic material as an invitation into the deeper mysteries of heterodox theology. Though idiosyncratic, his approach to esotericism clearly reflected his membership in the Moorish Orthodox Church of America.

Fig.4: Irsay (right) joined the WBAI staff in the mid-1970s after returning from his travels in the East. He brought his experiences abroad to bear show, Primary Sources, which delved into obscure ancient texts.

Primary Sources maintained two important features of Radio Unnamable. First, Irsay interspersed free-form discussions with callers within his exacting textual criticism, which reflected the interactive style of radio that Fass had pioneered. Second, and more importantly, Irsay’s forays into the ancient heresy illustrated the historical continuity that linked the “illuminated” imagination of psychedelicism to the much older tradition of spiritual anarchism. Here, it is important to emphasize that Irsay did not link his on-air forays into religious heterodoxy to the illuminated politics of the Yippies. Unlike his predecessor, Irsay was not a Yippie partisan, nor he did not use his show as a grandstand to preach any form of militant radio psychedelicism. Primary Sources did not push any agenda, but instead offered the listeners a vista into its hosts’ own intellectual obsessions, which often included orthodox religious texts as well. While it would be too much to claim that Irsay’s program carried the torch for Fass’s psychedelic evangelism, its exegetical focus ultimately created an opportunity for another member of the MOCA, Peter Lamborn Wilson, to launch his own radio crusade.

The MOCA radio crusade was resuscitated in June of 1987, after Irsay embarked on a three-month archaeological expedition in Israel. As a replacement, he tapped Wilson to act as his substitute that summer. The two had been dear friends since their days in the MOCA, and became even closer after sojourning in India together in the early 1970s. Wilson’s good humor and scholarly caste of mind made him a natural fit for the provocative scholasticism the listeners of Primary Sources had grown to expect. Wilson’s stint on the show, from June through August, was a success thanks in large part to his extensive first-hand experience with religious heterodoxy. Whether discussing sacramental hashish use among Qalandariyyah Sufis, or the internecine disputes of British Chaos Magicians, Wilson was able to add an insider’s take on the matter. Moreover, he also expanded the general focus of the show to include esotericism from the Far East, which contrasted starkly with Irsay pronounced preference for Jewish and Christian esoterica. Effortlessly drifting from ancient Daoism to Beat Zen, from Islamic magic to Javanese dance, Wilson’s evident expertise was suffused with the intangible quality that distinguishes actual understanding from mere knowledge.

Across the summer, Wilson transformed Primary Sources into a clearing house for an emerging late-1980s culture of militant psychedelicism. By this time, the spirit of revolt once led by the Yippies had been beaten into retreat by the federal government’s domestic “war” on drugs. Wilson’s shows served as a radiophonic outpost of resistance during this repressive period. In this section, I will examine three broadcast events that took place on MORC, and which embodied the embattled state of psychedelicist militancy at the turn of the Millennium.

Peter Lamborn Wilson’s Primary Sources

Wilson began his career as a broadcaster after a decade of spiritual adventuring in faraway lands. His protracted period of sojourning- as well as the vast reserve of esoteric lore he had amassed - won him the reputation of being the ‘Marco Polo’ of 1980s radicalism (Black, 1989: 214). A full-time member of the psychedelic colony in New York City, Wilson chose self-exile, that is to say he “dropped out” of America after the paroxysm of state violence that exploded at the Yippie’s Festival of Life held outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago (Versluis, 2010: 140). Alongside thousands of spiritual seekers, he trekked the overland passage across Europe to the seat of mystical knowledge in the East. While drifting in search of the sacred, he availed himself of a variety of exotic intoxicants (including opium, charas, and bhang), as well as numerous religious teachers. In India, for example, he became a disciple of the famous ganja-guru Ganeesh Baba (1890-1987), and not long thereafter, he received a personal initiation into Tara Tantra by Sri Kamanaransan Biswas. As recounted in his charming travelogue “My Summer Vacation in Afghanistan,” Wilson continued on to visit numerous Hindu and Islamic pilgrimage sites, whereupon he was joined by Irsay, who had likewise expatriated in search of authentic sources of mystical illumination (Wilson, 2009).

Fig. 5: Attributed to Hakim Bey, Chaos articulated a new paradigm for cultural activism for the 1990s. Under the aegis of "ontological anarchism," Wilson outlined a militant philosophy of psychedelic illumination, free love, and "poetic terrorism".

Wilson spent the early 1970s wandering what became known as the “hash trail” that snaked through Nepal, the Indian Subcontinent, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Turkey, North Africa, and into Persia. Long enchanted by heterodox Islamic sects (especially the legendary Hashashin), Wilson was driven by the desire to make contact with an authentic Sufi order. His search finally came to an end in Iran, whereupon he was inducted into a branch of the Maryamiyya, a Sufi order founded by Frithjof Schuon (Ibid, 141). Beside his initiation, Wilson was offered a position at the Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy, run by Seyyid H. Nasr, the muqaddam of the order in Tehran, as well as an eminent historian of Islamic culture (Wilson, 2018). Wilson’s membership in the order, as well as his position at the academy, placed him at the heart of Traditionalism, an anti-modern (and in some cases re-actionary) school of metaphysics. According to Mark Sedgwick, the Iranian Academy was “the most important Traditionalist institution of the twentieth century,” a claim made evident by their staff of distinguished scholars, such as Toshihiko Izutsu and William Chittick (Sedgwick, 2004: 155; Versluis, 2010: 141). It bears mentioning, that many of the members of this faculty were not a part of the Maryamiyya order. Such was the case with Henry Corbin, who exerted the most lasting influence on Wilson. After the fall of the Shah in 1979, Wilson fled Iran to the UK where he published a lavishly illustrated book on angels. While living in London, Wilson grew increasingly disillusioned with Schuon’s teachings, and finally left Maryamiyya order in opposition in 1981, just before repatriating back to New York City where he reconnected with Irsay (Greer, 2014b).

The air of secrecy that enshrouded the Maryamiyya order prevented Wilson from discussing it on air. However, he did comment on his personal dealings with other Sufi sects, including the Chishtī Order and the Nimatullahi. In addition to featured selections of music from around the world ranging from Turkish janissary marches to medieval English folk tunes, Wilson’s earliest appearances on Primary Sources were dominated by discussions of the intersection between Eastern esotericism and the latest breakthroughs in Chaos science (i.e. Georges Cuvier’s catastrophism, IIya Prigogine’s dissipative structures, etc.); however, this topic soon gave way to an entirely different domain of esoteric knowledge. As the summer rolled along, Wilson dedicated the program largely to his reflections on the subterranean world of fanzine publishing. From the dawn of its efflorescence in the mid-1980s, this decentralized amateur publishing network encompassed tens of thousand of publications that were never available to the reading public. Over the course of the summer, Wilson converted Primary Sources into his own viva voce publication. Enmeshed in this underground network, the program included zine reviews, discussions surrounding radicalism within the zine scene, and it provided the information necessary for listeners to become involved. Wilson was especially well-positioned to comment on the literary microcosm because, unbeknownst to his listening audience, he moonlighted as one of its luminaries, Hakim Bey (Black, 1994: 105).

Wilson’s career in the zine scene began three years before his stint on Primary Sources. He debuted under the nom de guerre Hakim Bey with an incendiary erotico-visionary prose-poem, Chaos (1984), which was not unlike Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass (fig.5). Under the guise of this anarcho-Sufi propagandist, Wilson authored a number of essays, or “communiqués” that were widely reprinted across the zine scene, and offered a doctrine of psychedelicist militancy that was far more coherent than anything produced by his Yippie forbearers. Bey’s doctrine of Ontological Anarchism redefined Flower Power according to two tactics: Art Sabotage and Poetic Terrorism. While distinguishing between these tactics is beyond the scope of this paper, both aimed to produce an aesthetic shock that would, if executed correctly, instantaneously blasted open what Aldous Huxley referred to as the “doors of perception”. Ontological Anarchism (later adjusted to “Ontological Anarchy”) aimed not to harm one’s opponents, but to illuminate them. Going beyond conventional styles of protest, Ontological Anarchism offered zine scene radicals a revitalized doctrine of illuminate politics (Greer, 2014a). The writings of Hakim Bey elicited a sizable amount of attention in the zine scene, and this fanfare materialized as an ample supply of publications for Wilson to discuss during his summer stint on Primary Sources.

Fig. 6: Semiotext(e) USA mapped the intellectual topography of an underground world that laid below the placid surface of 1980s America. Long out of print, this compendium offers a comprehensive glimpse into a multifarious culture of dissent.

As a radio broadcaster, Wilson did more than merely introduce his listeners to the subterranean culture of 1980s radicalism. In a manner that was reminiscent of Radio Unnamable, his programs served as a launching pad for the emotionally arousing events that were crucial in the formation of a shared identity among the decentralized network of epistolary correspondents that made up the zine scene. Among his most significant interventions was the publication of Semiotext(e) USA (1987), which he announced on his show (fig.6). This text was the first mass-market anthology of material culled directly from the zine scene. Totaling over three-hundred and fifty pages, it contained material that was no less unnamable than the contents of Fass’ show. Pieces from all the modern psychedelicist religions were included, such Hakim Bey’s Chaos, the ranterish “brags” of the Church of the SubGenius, as well as numerous pieces from the Discordian Society. Intended by its editors to be a turning-point in the American culture of radicalism, this anthology presented mainstream audiences with strains of radicalism formerly confined to the cultural margins. Moreover, in keeping with the ethos of the zine scene, Semiotext(e) USA was designed to dissolve the boundaries between reader and writer. Concluding with a directory of over two hundred and fifty addresses, the anthology invited readers to contact the contributors directly. As a roster of the brightest stars in the zine scene, this directory provided a register of the self-styled “marginal milieu,” the vanguard that re-inaugurated the cultural revolution formerly exemplified by the Yippies.

Wilson was a co-editor of Semiotext(e) USA, and to celebrate its official release, he invited his editorial associates, Sue Ann Harkey and Jim Fleming, as guests on the show. This trio spent three years scouring the vast expanses of the zine scene for the material that ultimately ended up in the anthology, and as such, their conversation on air offered an unmatched level of insight into the cultural avant-garde embodied by the marginal milieu. Totally ignored by the mainstream media outlets, the book failed to spark the cultural insurrection imagined by its editors; nonetheless, it revealed the existence of an otherwise invisible culture of rebellion that Wilson would continue to nurture whilst on the air.

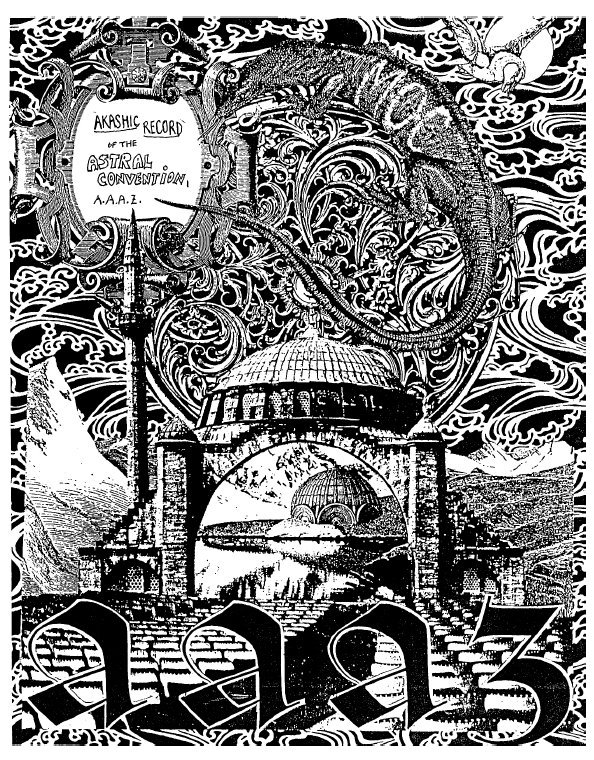

Fig. 7: Wilson and Dugwyler requested party-goers mail them an account of their experiences at the AAAZ so that they could compile a record of the astral jamboree. The duo received dozens of essays and pictures sent by some of the most recognizable figures in the zine milieu. Some months later, The Akashic Record of the Astral Convention (above) was distributed to the astral travelers who sent in their accounts.

Around this same time, Wilson orchestrated his own be-in style event for the marginal milieu, which he promoted across his live broadcasts that summer. Another first in this underground culture, this event is perhaps the clearest indication of the resonance between Primary Sources (under Wilson’s control) and Radio Unnamable. Assisted by Yael Ruth Dragwyla, arguably the marginal milieu’s most accomplished magician, Wilson staged The Antarctic Astral Autonomous Zone (AAAZ), a massive gathering scheduled to take place on the astral plane on the night of August 31st – September 1st. The venue they selected was a crystal minaret located in the Palmer Peninsula on extreme southern tip of Antarctica. As the zine scene’s first mass rally, the AAAZ represented a high-point of communitas in this decentralized community in much the same fashion as the be-ins of yore. Wilson promoted the event both on his show and, along with Dragwyla, in a number of marginal zines, such as Joel Biroco’s Chaos, Rev. Crowbar’s Popular Reality, and the FreFanZine APA. In addition to outlining the basics of astral travel, their public notices requesting all participants to compose short essays documenting their experiences at the astral gala. The anthologized account (fig.7) that appeared in the weeks following the event contained many of the authors that appeared in Semiotext(e) USA, particularly those associated with the occult.

Some years later, Wilson (writing as Bey) authored an extended essay outlining the theory behind the praxis embodied by the AAAZ. His most famous publication to date, “The Temporary Autonomous Zone” (1991) became a milestone within late twentieth century psychedelicism, and rave culture in particular (Gibson, 1999: 22). At the heart of the essay is a reconceptualization of the be-in, which Wilson placed into a theoretical framework that was explicitly anarchist. Unlike the be-in, which was fundamentally focused on sharing love, the Temporary Autonomous Zone (or T.A.Z) was described as a liminal social space outside the prevailing social systems of control. In Wilson’s reconceptualization, the focus is shifted from love to the inability of love to flower within the dominant social order. Wilson’s reconceptualization of the be-in in more explicitly anarchist terms was evidence of a larger trend in psychedelicism. This intensification of psychedelic militancy was best illustrated in Wilson’s on-air interview with Robert Anton Wilson (fig.8), chief spokesman for the Discordian Society, that August. Their conversation represents a high-point for the discourse of psychedelic militancy.

Peter Lamborn Wilson and Robert Anton Wilson (no relation) were giants in the marginal milieu. Though unknown to mainstream audience, Robert Anton Wilson was the co-author (with Robert Shea) of the Illuminatus! trilogy (1975), a pulp fiction masterpiece that became a touchstone for post-1960s psychedelia. Ostensibly a Discordian recruitment ploy, the trilogy mixed conspiracy theory, occult lore, with high camp sexplotation to form a wildly entertaining revisionist history of the psychedelic revolt of the 1960s. Displacing the Discordian holy books authored in the mid-1960s, this fanciful re-telling of the recent past became the basis for the Discordian worldview that would spread among heads in the decades that followed with increasing success. In the wake of Illuminatus!, Wilson went on to independently author two more Discordian trilogies, as well as a trio of memoirs under the name Cosmic Trigger (1977, 1992, 1995). That said, his appearance on MOCA was prompted by the publication of Semiotext(e) SF, an anthology of avant-garde science fiction authored within the marginal milieu, which he co-edited with Peter Lamborn Wilson. Though a work of outstanding artistry, the anthology proved far too experimental for mainstream audiences.

Over the course of Robert Anton WIlson and Peter Lamborn Wilson's two-hour on-air exchange, they offered an intimate look at the obscure persons, ideas, and events that characterized psychedelicist radicalism as of 1987. During their conversations, these men traced the genealogy of their own illuminated politics, beginning with early 20th century individualist anarchism, up through the psychedelic era (both had spent time at Millbrook), and far into the future, which they imagined in cyberpunk terms. It was clear, even then, that their lively conversation represented an invaluable literary document, as it elicited a sizable response from listeners. In fact, the demand for copies of the show prompted WBAI to issue special cassette tape recordings as a premium for its highest-level contributors.

Fig. 8: Though all members of the Discordian Society are honored as Popes, Robert Anton Wilson was regarded as the Pope of Popes. Over countless essays, novels, & autobiographies, Wilson sculpted Discordianism into a robust panoply of esoteric lore, cutting-edge scientific theories, and gut-busting humor.

Their conversation was less like an interview than a synod for contemporary psychedelicism. Discordianism, the brand of psychedelic militancy promoted by Robert Anton Wilson, shared many of the same fundamental assumptions as Ontological Anarchism, which Wilson continued to outline in his writings throughout the 1980s, and 90s (Greer, 2016.) Though internecine disputations were exceedingly rare between psychedelicist fellowships, the degree of solidarity shared by these lysergic patriarchs was significant. Their accord reflected the dire cultural situation of psychedelicists during the federal government’s War on Drugs campaign, which was an incredibly dark (but fertile) period for lysergic radicals. The threat of persecution loomed like a dark shadow over their dialogue, and undoubtedly motivated them to turn their conversation away from LSD and towards the spate of technological devices known as “mind machines” then being promoted as viable alternatives to psychedelic drugs. Though friends and fellow-travelers, the two profoundly disagreed about the role of technology in the expansion of consciousness: in short, Robert Anton Wilson was a committed futurist and Peter Lamborn Wilson was a confirmed luddite. Disagreements aside, their conversation clarified, in exacting detail, the discourse of psychedelicism just before the turn of the millennium.

The Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade

Wilson was offered his own show after Irsay returned from Israel. Following a five month hiatus from broadcasting, Wilson returned to the air with Moorish Orthodox Radio Hour, which debuted in January, 1988. Broadcast every other Tuesday from 12 a.m. to 2 a.m., the show ran for some months before Wilson changed the name to The Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade (MORC). Wilson’s decision to re-use the name of the radio program his church had broadcast on WBAI back in the 1960s was a reflection of his larger efforts to resuscitate the Moorish Orthodox Church of America. Undoubtedly inspired by his growing popularity in the marginal milieu, Wilson’s decision to revive the church was also influenced by the centennial celebration of Noble Drew Ali (1886-1929), the prophet of Moorish Science (Bowen, 2015: 320-321), staged in 1986.

Fig. 9: Peter Lamborn Wilson composed a zine during his stint on the show, entitled The Radio Sermonettes (later re-published by AK Press in 1994 as Immediatism). Attributed to The Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade Collective, this work describes the text as a collaboration between Peter Lamborn Wilson, "The Army of Smiths" (Dave, Sidney, Max), Hakim Bey, Jake Rabinowitz, Thom Metzger, Dave Mandl, and James Koehnline. The text featured a selection of some of Wilson's favorite on-air discourses.

The Moorish Science movement led by Noble Drew Ali was officially launched in 1913. The religion spread rapidly in the wake of the Great Migration in which millions of black people relocated from the rural South into urban centers in the North. In terms of doctrines, Moorish Science combined New Thought teachings concerning the realization of the “higher self” with the ornamental trappings of irregular Freemasonry (Nance, 2002: 123-166). Within this system, the higher self was linked to the recovery of the Moorish heritage that European slave-owners had stripped from black people in their passage to the Americas. At the heart of Moorish Science was, then, a rejection of the label of “Negro” in favor of the lost and altogether more sacred Moorish heritage of black people. Despite its overt use of Islamic terminology, though, Noble Drew’s distinctly American religious teachings borrowed more from the local context of black migrants than the Islam tradition of the near East. This is perhaps best demonstrated in the Circle Seven Koran (1928), the testament to Moorish Science, which Noble Drew’s constructed from sections appropriated from H. Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus Christ (1920) and the Rosicrucian treatise Unto Thee I Grant (1925) (Gomez, 2005: 232). Altogether, Moorish Doctrine compelled all Noble Moors to live by the principles of “Love, Truth, Peace, Freedom, and Justice”.

Admission in the Moorish Science movement was traditionally restricted to African Americans. As such, the Moorish Orthodox Church of America was something of an anomaly insofar as its dozen or so members were predominately (but not exclusively) white hipsters. The roots of the church reach back of an older beatnik Moorish order, The Noble Order of Moorish Sufis, which Rafi Sharif (b. Jean Singer) had formed in Baltimore in the mid-1950s. Sharif was one of the few white people admitted into the Moorish Science movement, and he founded his order as a means of spreading the teachings of Noble Drew beyond its traditionally racial constituency. This minority branch of the Moorish movement was carried to New York City by the jazz musician and poet Walid al-Taha (b. Warren Tartaglia), who introduced it to a small group of Columbia University students, and self-admittedly "LSD-crazed" hipsters that included Peter Lamborn Wilson (Wilson, [?]). This circle of friends saw in Noble Drew’s teachings a means of disaffiliating with the “square” culture of their race, a maneuver that the aforementioned John Sinclair would repeat a few years later when he formed the White Panther Party. Absorbing a promiscuous variety of influences, MOCA affirmed an alternative religious identity that wove together Eastern teachings from Sufism, Advaita Vedanta, and Tantra, with decidedly American influences such the Beat writings of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac. Walid al-Taha’s Moorish doctrines also incorporated the political philosophy of anarchism, and following their “sheik” Rafi Sharif, members of the church joined the Industrial Workers of the World, America’s oldest anarcho-syndicalist union. The MOCA adopted as their banner the winged heart with crescent and star symbol popularized by the Sufi musician Hazrat Inayat Khan, and a few years later, Wilson received belated permission for this appropriation by Hazrat's successor, Pir Vilayat (Ibid).

After his death in 1989, Bishop Itkin was consecrated "Saint Mikhail of California" by the MOCA. The church has canonized hundreds of other saints (one for each day of the year), which are memorialized in its popular Jubilee Saints Calendar.

Undoubtedly, the most perplexing aspect of this church concerns its claim on “orthodoxy”. The “orthodox” aspect of their beliefs was derived from a heterodox branch of the Old Catholic Church, which was itself a heretical offshoot of the Roman Catholic Church. Formed in opposition to the doctrines of the First Vatican Council (and particularly papal infallibility), the Old Catholic Church was populated by a number of episcopi vagantes, or “wandering bishops” that roamed the world establishing their own independent churches (Itkin, 2014). The MOCA became entangled in this heterodox Christian movement through one such bishop, Michael Itkin (fig. 10), who played an integral role in the wider gay catholic underground that emerged in the second half of the twentieth century (Itkin, 2014). Rafi Sharif formally exchanged religious titles with Itkin (later consacrated a saint by the MOCA) sometime in the early-1960s, which led to the cross-initiation of the hipster Moors with the Orthodox Catholic Church (Wilson, 2018). Not long thereafter, the MOCA filed incorporation papers within Dutchess Co., New York, and in so doing became a formally recognized church entity.

Aside from being hipsters, the MOCA further differentiated themselves from the larger Moorish movement by virtue of their sacramental view of psychedelics, including cannabis, peyote, and LSD. These Moors did not simply use psychedelics, they distributed them as “sacraments” throughout the bohemian colonies that sprouted across Manhattan and over into Brooklyn. As an aside, the official sacrament of the church was cannabis, which was used in far greater proportion than any of the other psychedelics (Wilson, 2018). As distinct from the ruthless criminality that often typifies the drug trade, their reverential approach to psychedelics reflected what the anthropologist Lewis Yablonsky termed “righteous dealing,” an outlaw religious custom typical of psychedelic churches that entailed the low cost (or free) distribution of high-quality psychedelics in the name of universal love (Yablonsky, 1968: 50-52). The risk associated with distributing the sacraments placed the MOCA on the front lines of a spiritual battle against the dominant social order, and their reputation for righteousness eventually led to an alliance with The Sri Ram Ashram and The League of Spiritual Discovery, both based at the Millbrook estate. (A member of MOCA, Abu Yazid Scully [b. Tim Scully], occupied one of the much-coveted rooms in the mansion that sat at the heart of the 64-acre Millbrook estate. [Wilson, [?]]) Unlike the League and countless other psychedelic sects, though the MOCA did not dissolved in the early 1970s, but instead went into a state of suspended animation as the US government intensified their persecution of drug-users.

Fig. 10: Bill in the WBAI studio. Recently, he has revived MORC as a podcast, Countervortex.

Since there are no recordings of the original Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade, it is impossible to compare it to the revitalized edition of the show that Wilson launched in 1988. Nonetheless, it is fairly clear that the new iteration was much more involved in the local anarchist scene than its predecessor. The focus on radical politics became much more pronounced in 1992, after Wilson accepted Bill Weinberg as his understudy and technical engineer. Together, they made MORC a sounding board for New York City’s vibrant anarchist scene, as well as the otherwise secret history of resistance to the Spectacle of late modern Capitalism. Weinberg had met Wilson through their mutual participation in the Libertarian Book Club, an anarchist forum founded in the 1940s by veterans of the Golden Age of anarchism. Both men had spent years within the anarchist milieu, though it bears mention that Weinberg emerged from more activist-oriented circles, whereas Wilson was much more committed the utopian dimension of the tradition. Perhaps it is this distinction that accounts for their dramatically different broadcasting styles. In contrast to Wilson’s free-form monologues, Weinberg favored investigative reportage. Amongst his journalistic achievements, Weinberg was the first North American reporter to travel into the EZLN-controlled region of Chiapas (Mexico) and interview the Zapatista icon Subcomandante Marcos.

The MORC collective grew once more in 1995 when Ann Marie Hendrickson joined Weinberg and Wilson as an on-air host. Hendrickson had been a guest on the show once before, as a representative for Neither East Nor West, an anarchist solidarity group that linked anti-nuclear activists in the US and Russia. The collective expanded once again to include Dave Smith as technical engineer, Max Schmid as producer, and Sharon Gregory as yet another co-host. Between the years 1995-2001, the six-member collective produced some of the show’s most diverse, and fascinating programming. In his conversations with me, Bill referred to this period as the “glory years” of the MORC.

The terrorist attacks on September 11th provide a convenient means of differentiating between the early and later periods of the show. As the nation fell into turmoil, Wilson’s appearances on the show became ever more infrequent, which was undoubtedly a major disappointment for many of the long time listeners. His departure, though, provided Weinberg with the opportunity to produce more elaborate programs, which resulted in an expansion of MORC’s listening audience. The show reached the height of its popularity between 2001-2012. During this period, there were steady improvements in the show’s production values, as well as a renewed sense of focus amongst the remaining MORC collective. While the show was always global in focus, the team of Weinberg, Hendrickson, and Gregory covered a wider swath of the antiauthoritarian movements neglected in the mainstream press.

The show was canceled in March 2011 after a controversy involving the premiums WBAI offered to its subscribers. The controversy itself need not concern us here, so suffice it to say that Radio Unnamable was also taken off the air after Weinberg attacked the station’s management on-air, which was a flagrant violation of the unspoken rules of broadcast radio. His intransigent diatribes lambasted the station for its unscrupulous fund-raising methods, its failure to dispense premiums to patrons in a timely fashion, and for its distribution of work created by the anti-Semitic author David Icke. The final live broadcast aired on March 15, 2011, after which point the show went into a brief period of “exile” on the internet before ceasing broadcasting altogether.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have traced a tradition of radio psychedelicism that connected Bob Fass’ Radio Unnamable (1963-1977), James Irsay’s Primary Sources (1977-1987), and Peter Lamborn Wilson’s Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade (1988-2012). My analysis has been admittedly limited, as I confined my focus to a succession of shows that occupied roughly the same timeslot (midnight-3am) on the same station (WBAI). Needless to say, there is still much that remains to be covered in the history of psychedelicist broadcasting. For example, directly following MORC was Margot Adler’s Hour of the Wolf, another WBAI program that showcased the interface between anarchism and heterodox spiritualty. Adler authored of one of the earliest sociological treatments of modern Paganism, Drawing Down the Moon, and she continued this work on her show, offered listeners a vital picture of the margins of American religion (Adler, 1979). Incidentally, she too interviewed Robert Anton WIlson on her show as well. Perhaps even closer to the tradition of psychedelicist radio, the Church of the SubGenius cultivated a diminutive broadcast empire throughout the late-1980s, which included the long-running The Puzzling Evidence Show, Ivan Stang’s Hour of Slack, and Dr. Howland Owll’s The Ask Dr. Hal Show. Airing alongside MORC, these programs guarded the flame of psychedelicism into its passage beyond the fin du millennium.

Today, there remain hundreds of tapes of MORC shows that have yet to be digitized. There is no way to expedite the translation of these programs from cassette to computer file: each side must be played at normal speed and flipped at the appropriate moment. Of course, the archival process is far more than the technical aspects involved in digitization. The intensive technical labor involved cannot be separated from the social aspects of the project. It is hard to relate the anticipation I felt before my weekly trips to Bill’s apartment that summer. He had taken the utmost care to preserve the MORC archive for more than two decades, and now, much to my delight, he was entrusting this legacy to me. He lent me the tapes roughly a dozen at a time, and it was no small thrill to ferry these priceless treasures alongside my fellow passengers on the subway as I headed back to my flat. The first fruit of our project was a collection of broadcasts entitled Gems from the Moorish Orthodox Crusade, which I uploaded on the open-access media repository Archive.org in 2014. Though I consider each episode a gem in its own right, these broadcasts shimmered with an undeniable brilliance on account of the virtuosity exhibited by the host, or hosts on that particular recording. It was with a large measure of pride that I observed the number of listeners rise from the hundreds to over a thousand in the months that followed.

During our regular appointments, Bill and I would review the contents of the recently digitized lot of episodes before moving on to the next stack. It would be too trite to say that we voyaged through the not-so-distant past of American cultural radicalism during our weekly sessions; however, through our collaboration I recognized that MORC was not simply a radio show- it was a masterwork, a grand opus of documentary evidence of the lived experience of rebel culture. Speaking to the mythic dimension of archival work, the choir of voices captured on those cassette tapes relates not simply what has been, but what could be.

[This essay would not have been possible without the assistance of numerous people. To start, the folks at Loroto were kind enough to teach me how to digitize cassettes & lend me the equipment necessary to do so. Bill Weinberg deserves special thanks for both opening his doors to a complete stranger, as well as trusting me with the MORC media artifacts. Similarity, a debt of gratitude is owed to Raymond Foye, who collected, preserved, & digitized Peter Lamborn Wilson's appearances on Primary Sources in the first place. His collection of MORC broadcasts represents an indispensable part of this archive. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge Peter Lamborn Wilson himself, who has been more than generous with his time reviewing this essay. That said, all the errors contained herein are solely my own.].

Bibliography

Adler, Margot. 1979. Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. New York: Viking.

Black, Bob. 1989. Rants and Incendiary Tracts: Voices of Desperate Illuminations : 1558-Present. New York: Amok Press.

Cottrell, Robert & Brice Browne. 2018. 1968: The Rise and Fall of the New American Revolution, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Fisher, Marc. 2006. “Voice of the Cabal,” The New Yorker, December 4th 2006: [online access].

Greer, J. Christian. 2014a. “Occult Origins of Hakim Bey’s Ontological Post-Anarchism.” Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies 3(2): 166-187.

Ibid, 2014b. “Hakim Bey,” The Occult World, (ed. Christopher Partridge) London: Routledge.

Ibid, 2016. "Discordians Stick Apart," Fiction, Invention, & Hyper-reality. (Eds. Carole Cusack & Pavol Kosnac), London: Routledge: 181-197.

Gibson, Chris. 1999. “Subversive Sites: Rave Culture, Spatial Politics and the Internet in Sydney, Australia.” Area 31(1): 19-33.

Gomez, Michael. 2005. Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grogan, Emmett. [1972] 2009. Ringolevio: A Life Played for Keeps. New York: NYRB.

Harder, Kelsie. 1968. “Coinages of the Type of ‘Sit-In,’” American Speech 43(1): 58-64.

Itkin, Mikhail. 2014. The Radical Bishop and Gay Consciousness: The Passion of Mikhail Itkin. Brooklyn Autonomedia.

Jarnow, Jesse. 2016. Heads: A Biography of Psychedelic America. Boston: Da Capo Press.

Lee, Martin & Bruce Shlain. 1985. Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD. New York: Grove Press.

Miller, Timothy. 1991. The Hippies and American Values. Knoxville: Uni. of Tennessee Press.

Nance, 2002. “Mystery of the Moorish Science Temple: Southern Blacks and American Alternative Spirituality in 1920s Chicago,” Religion and American Culture 12(2): 123-166.

Paglia, Camille, 2003. “Cults and Cosmic Consciousness: Religious Vision in the American 1960s,” Arion 10(3): 57-111.

Raskin, Jonah. 1997. For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman. Berkeley: Uni. of California Press.

Sedgwick, Mark. 2004. Against the Modern World: Traditionalism and the Secret Intellectual History of the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, John. [1972] 2007. Guitar Army: Rock and Revolution with The MC5 and the White Panther Party. Port Townsend, WA: Process Media.

Stevens, Jay. 1987. Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream. New York: Grove Press.

Urgo, Jospeh. 1987. "Comedic Impulses and Societal Propriety: The Yippie Carnival," Studies in Popular Culture 10.1: 83-100.

Versluis, Arthur & Peter Lamborn Wilson. 2010 “A Conversation with Peter Lamborn Wilson.” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 4.2: 139–165.

Walker, Jesse. 2001. An Alternative History of Radio in America. New York: NYUP.

Wilson, Peter L. [?] "Occult Moorish History of New York," unpublished.

Ibid. 2018. Personal interview conducted July 27th.

Ibid. 1991. Radio Sermonettes. New York City: The Libertarian Book Club.

Ibid. 1989. Scandal: Essays in Islamic Heresy. Brooklyn: Autonomedia.

Ibid, 1993. Sacred Drift: Essays on the Margins of Islam. San Francisco: City Lights Books

Ibid, 2015. Spiritual Journeys of an Anarchist. Berkeley: Ardent Press.

Yablonsky, Lewis. 1968. The Hippie Trip: A Firsthand Account of the Beliefs and Behaviors of Hippies in America By A Noted Sociologist. New York: Pegasus.

The Moorish Orthodox Radio Crusade was a collective composed of the following members:

Peter Lamborn Wilson ..... Hierophant Emeritus

Bill Weinberg ............................. Senior Ranter

Ann-Marie Hendrickson ..... Resident Athena

Sharon Gregory ..... Homebody Amazon (MIA)

Bob McGill ........... Engineer and Archeologist

Hakim Bey............ Spiritual adviser