Popular Reality: A Vital Organ for the ShiMo Underground

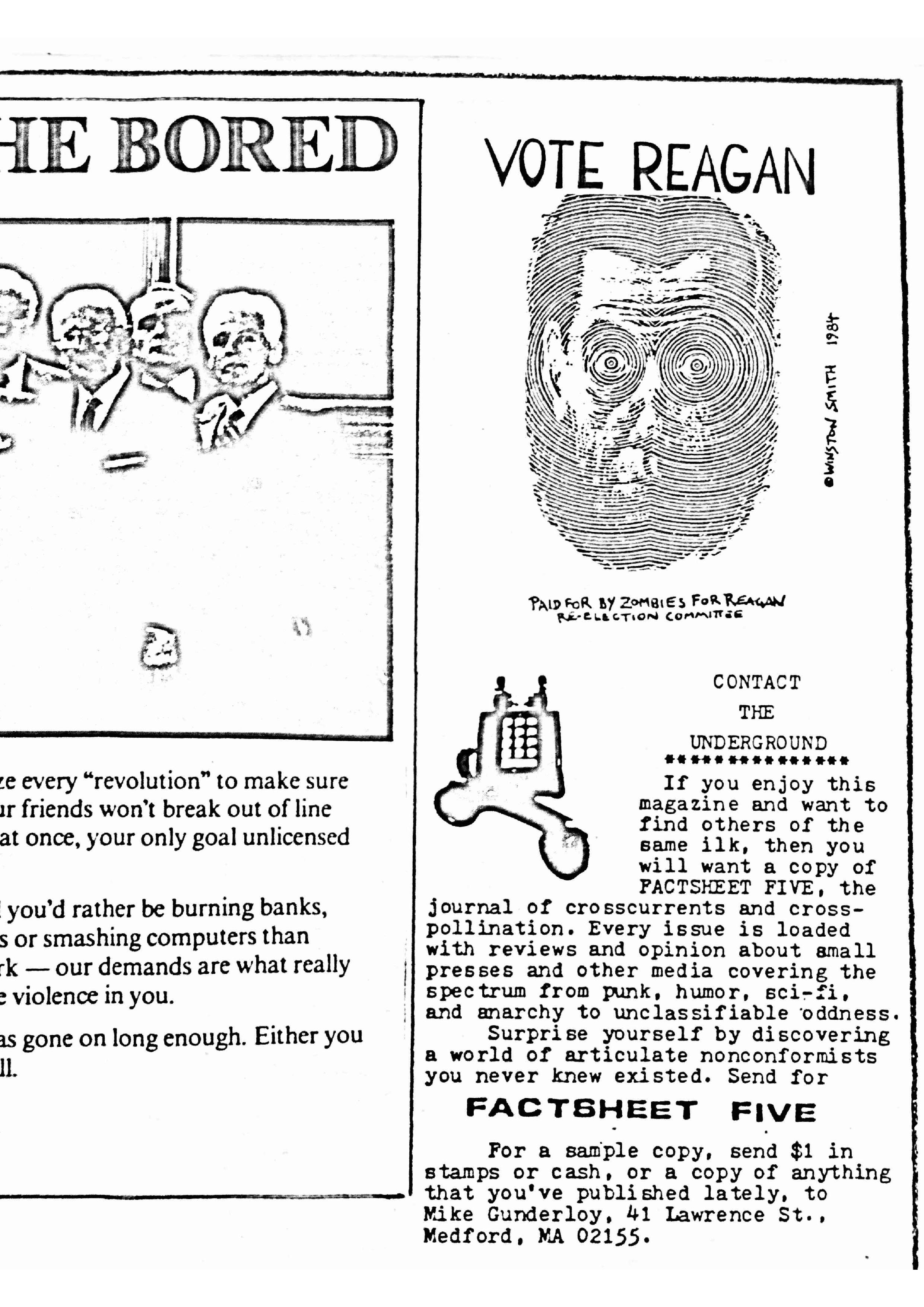

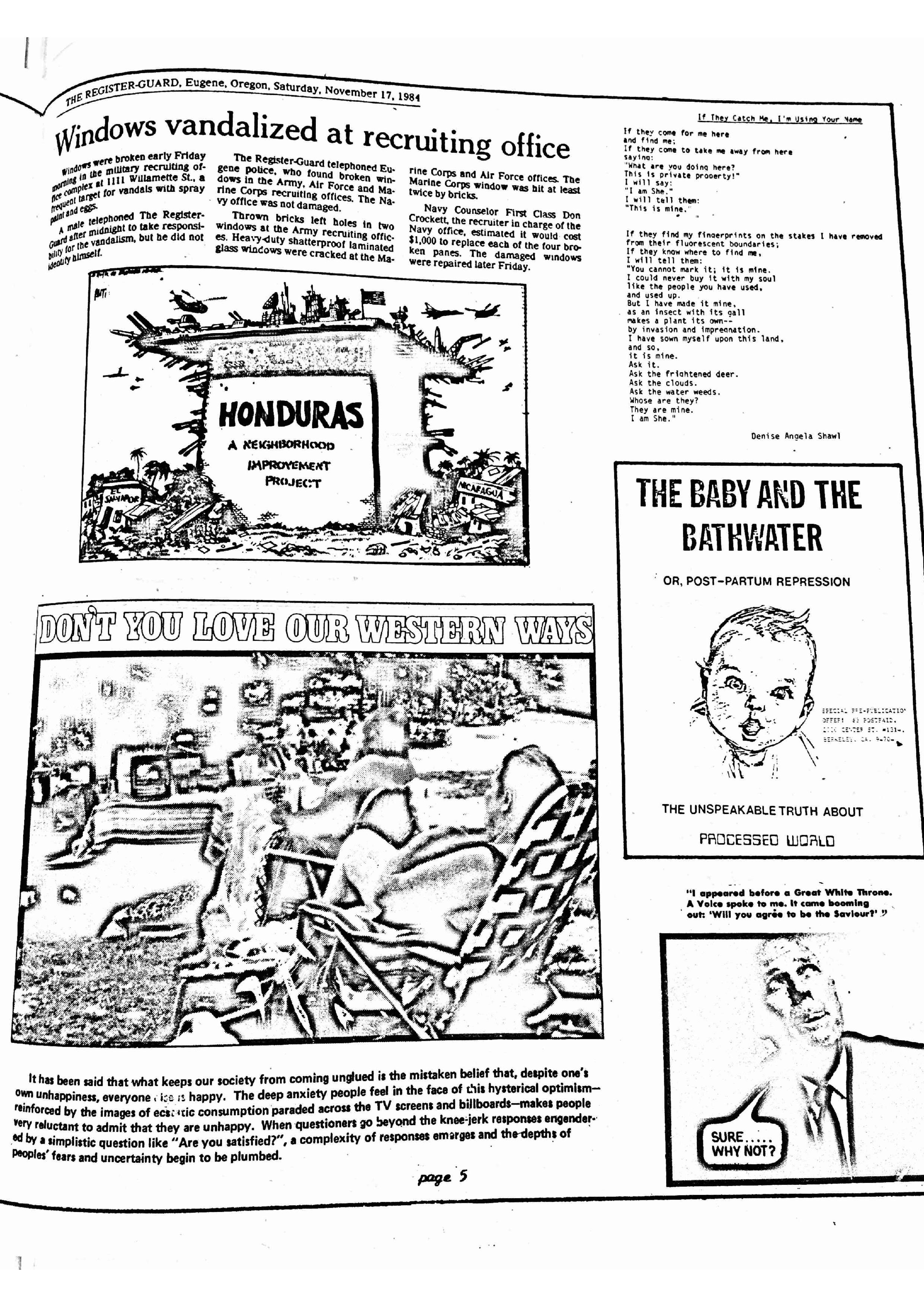

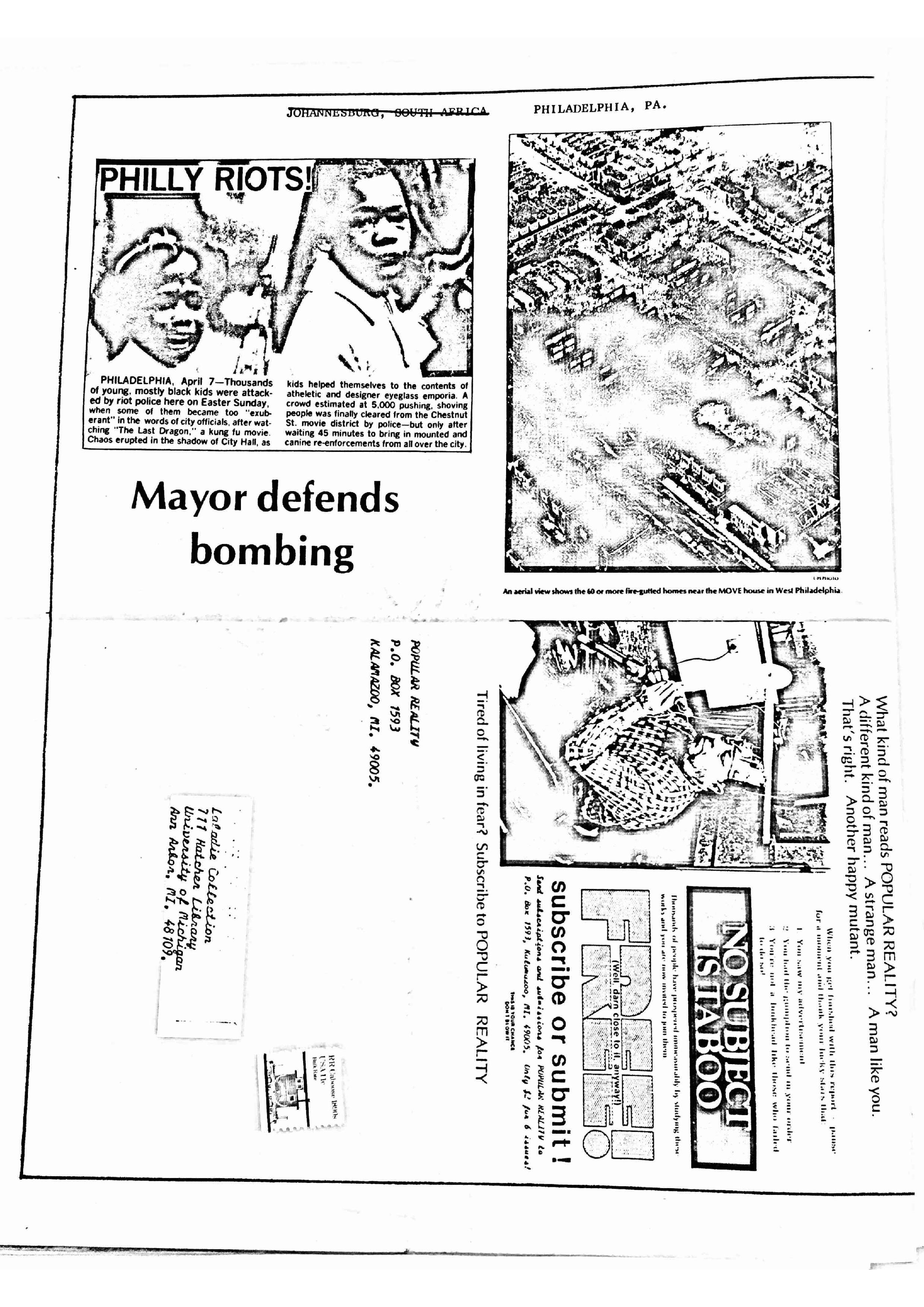

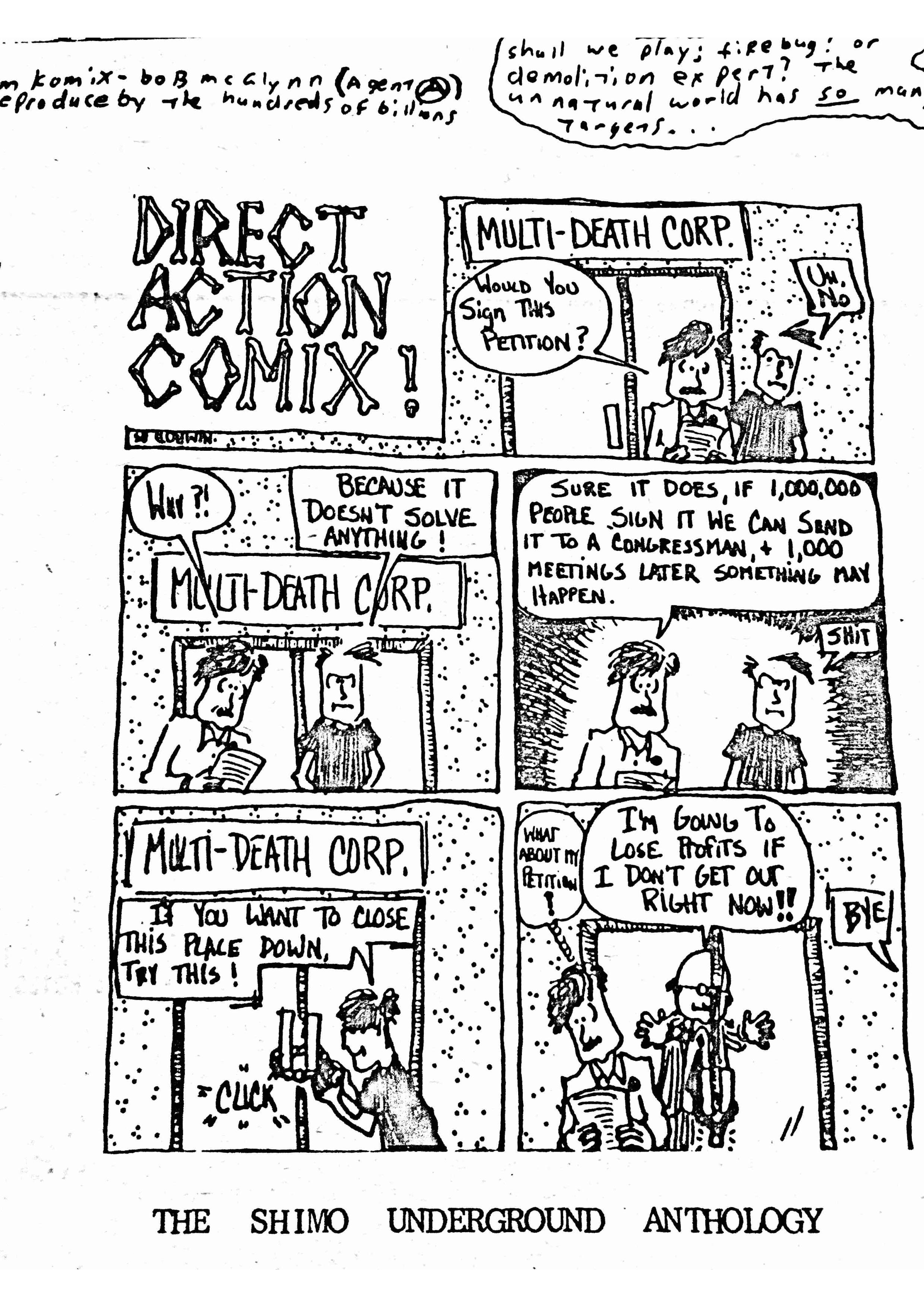

In 1984, Popular Reality started publication. This ominous year provided the perfect backdrop for the militant humor and furious delights that characterized this fanzine. Popular Reality was initially published as a dissenting voice within the peace movement, which led the way for anti-nuclear activism in the 1980s and 90s. Under the editorial directorship of Rev. Crowbar, the fanzine attacked the doctrinaire pacifism of the anti-nuke movement, which had internalized the puritanical, or “politically correct” ethos that had become normative within 1970s Leftism in North America. In Popular Reality, readers found the rigid moralism of the peace movement juxtaposed with the ideology of social nihilism, the unwieldy combination of acid communism, pro-Situationist analysis, and chaos magick promoted by Crowbar and the growing avant-garde of hip militants that coalesced within the literary microcosm of fanzine culture. The culture of fanzine exchange, or “zine scene,” burgeoned through the 1980s and into the late 1990s. Founded on the de-centralized exchange of self-printed publications through the mail, this bohemian Republic of Letters consisted of approximately 10,000 amateur self-publishers, who compiled and distributed voluminous amounts of fanzines, self-recorded audio cassettes, and art across the world. Within this expansive scene, Popularity Reality served as a rallying point for the “marginals milieu,” the heterogeneous cognoscenti whose writings on social nihilism sketched a new horizon of the hip militants on the ultra-left. Popular Reality No. 11 featuring a cover image of the Righteous Dervish, renegade SubGenius reverend and mastermind behind the PARTY WITH GOD campaign.

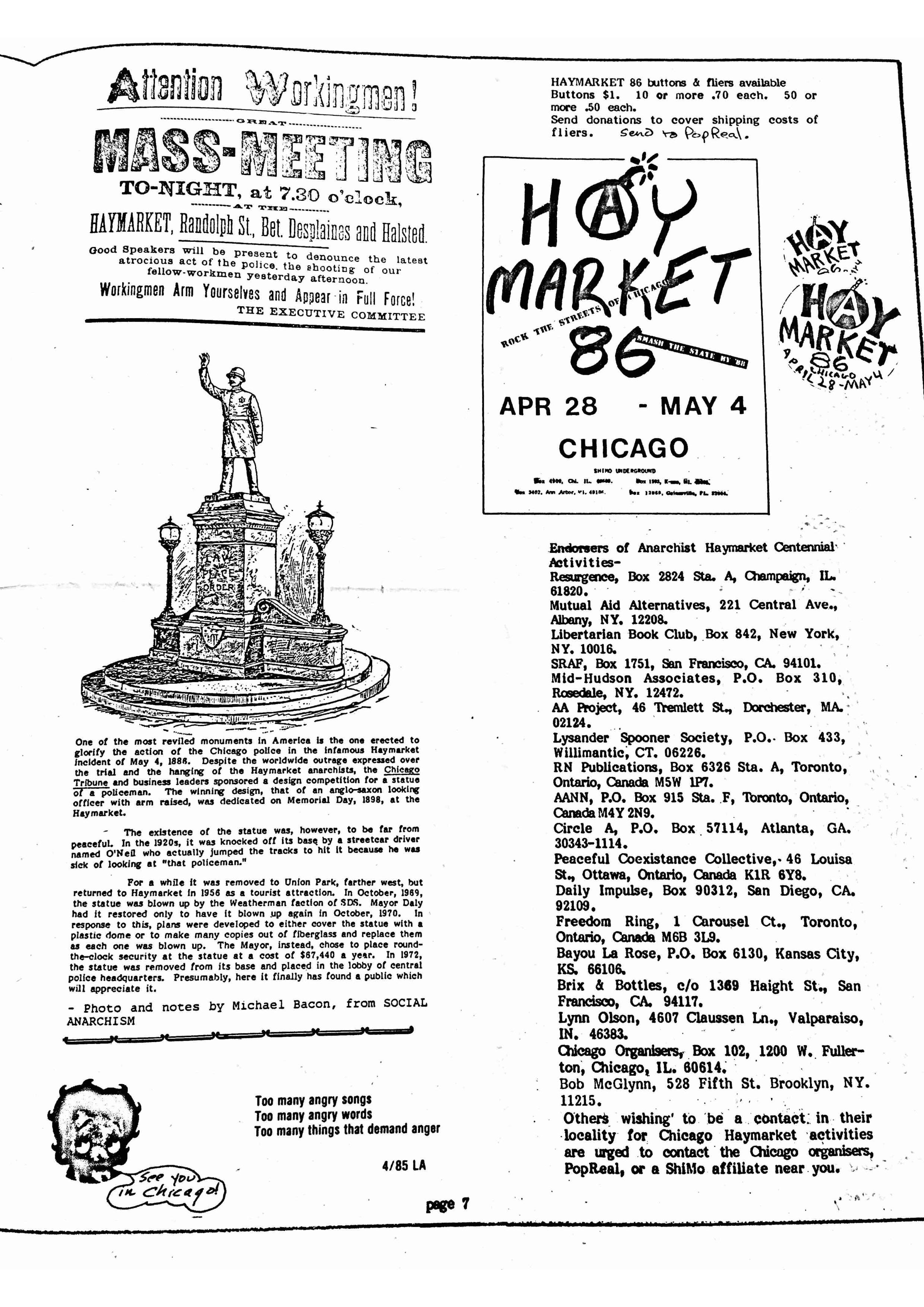

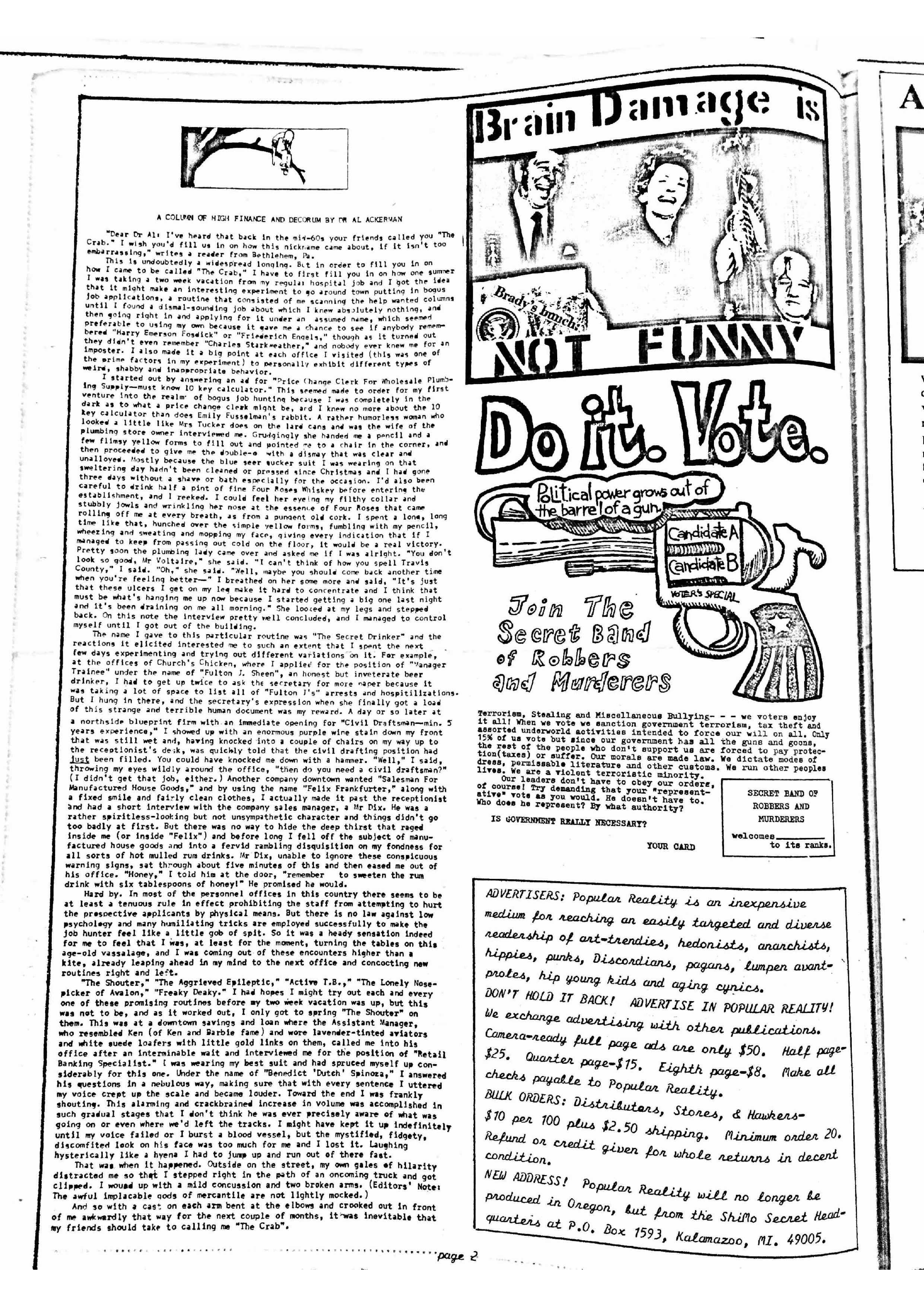

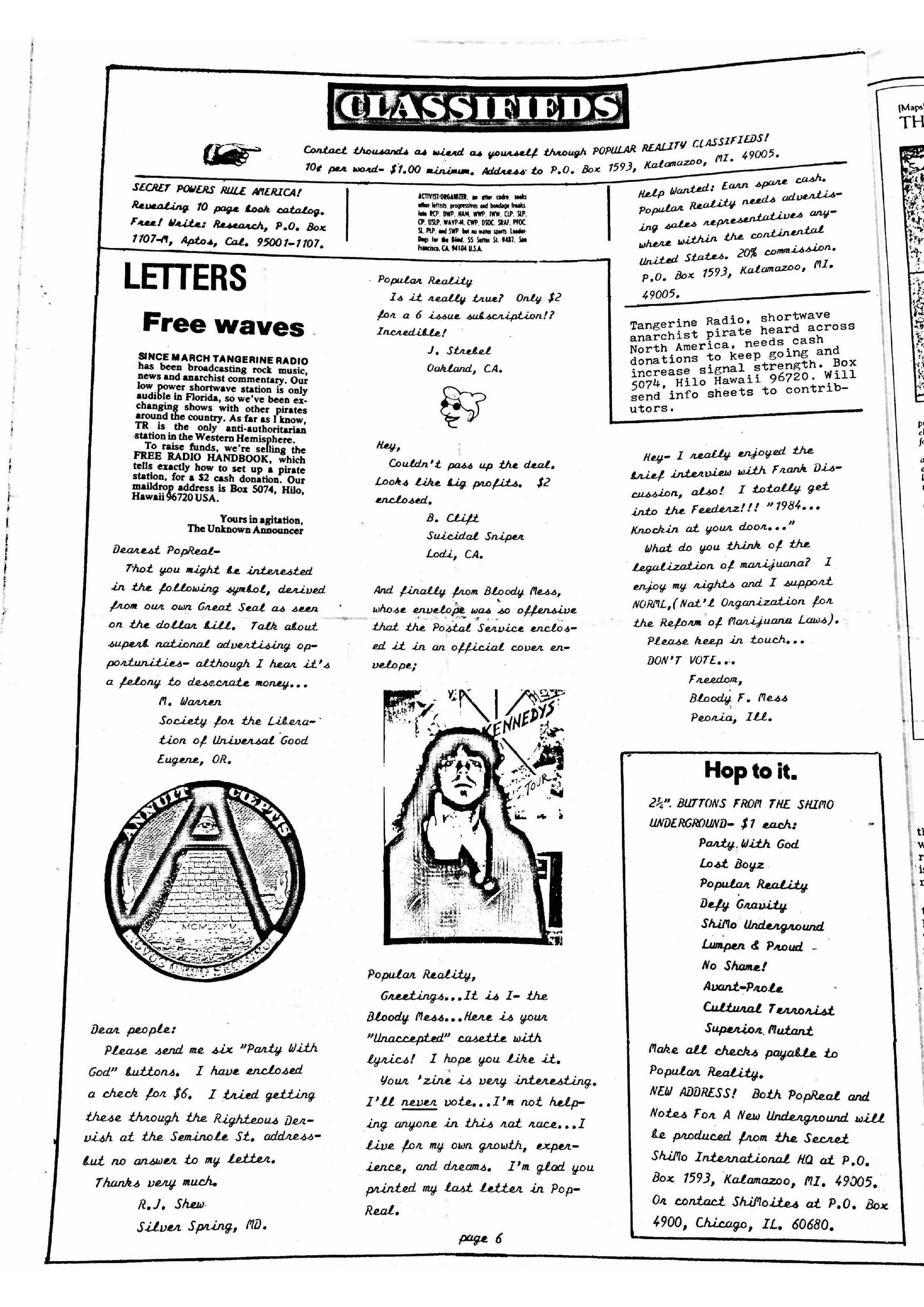

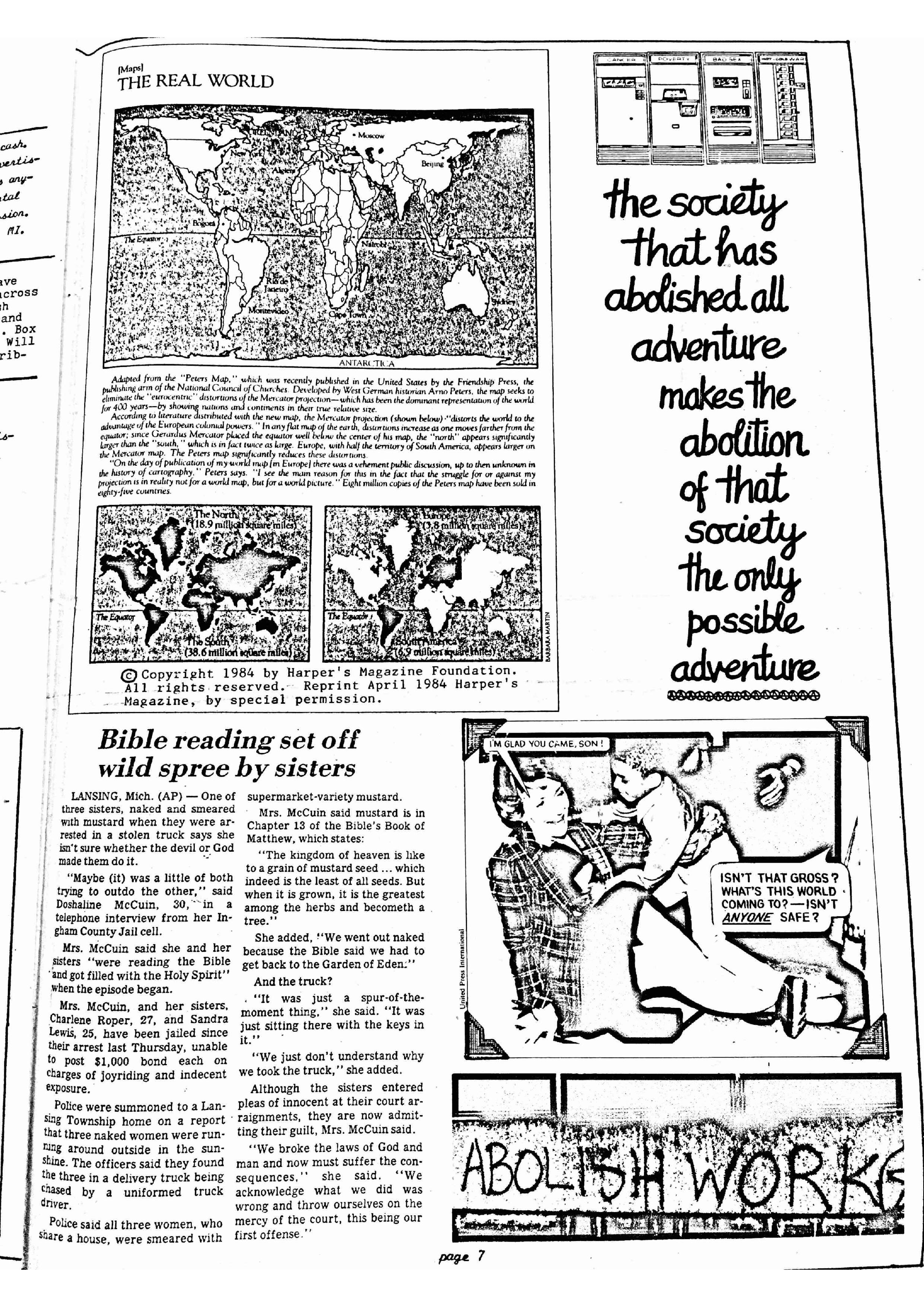

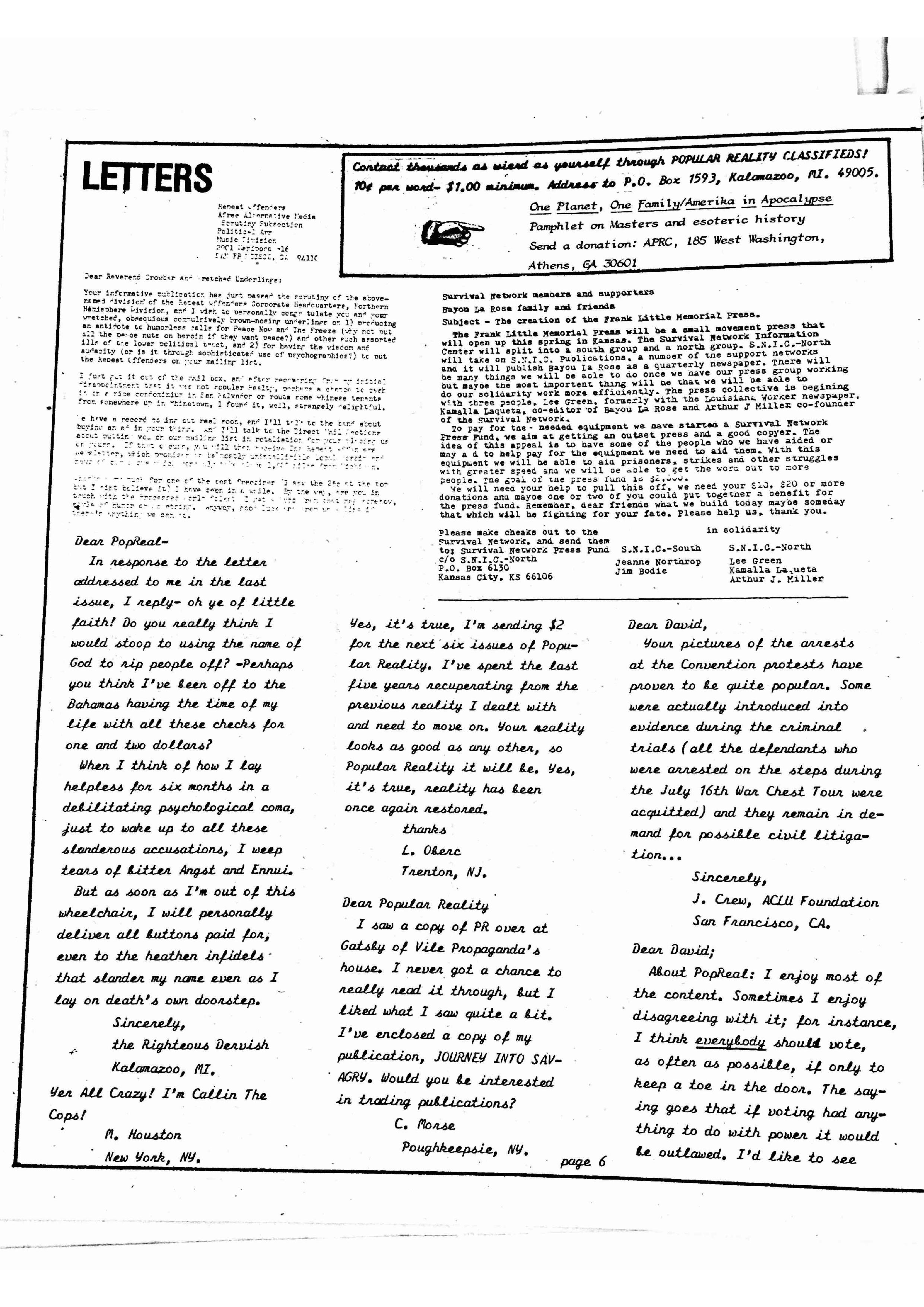

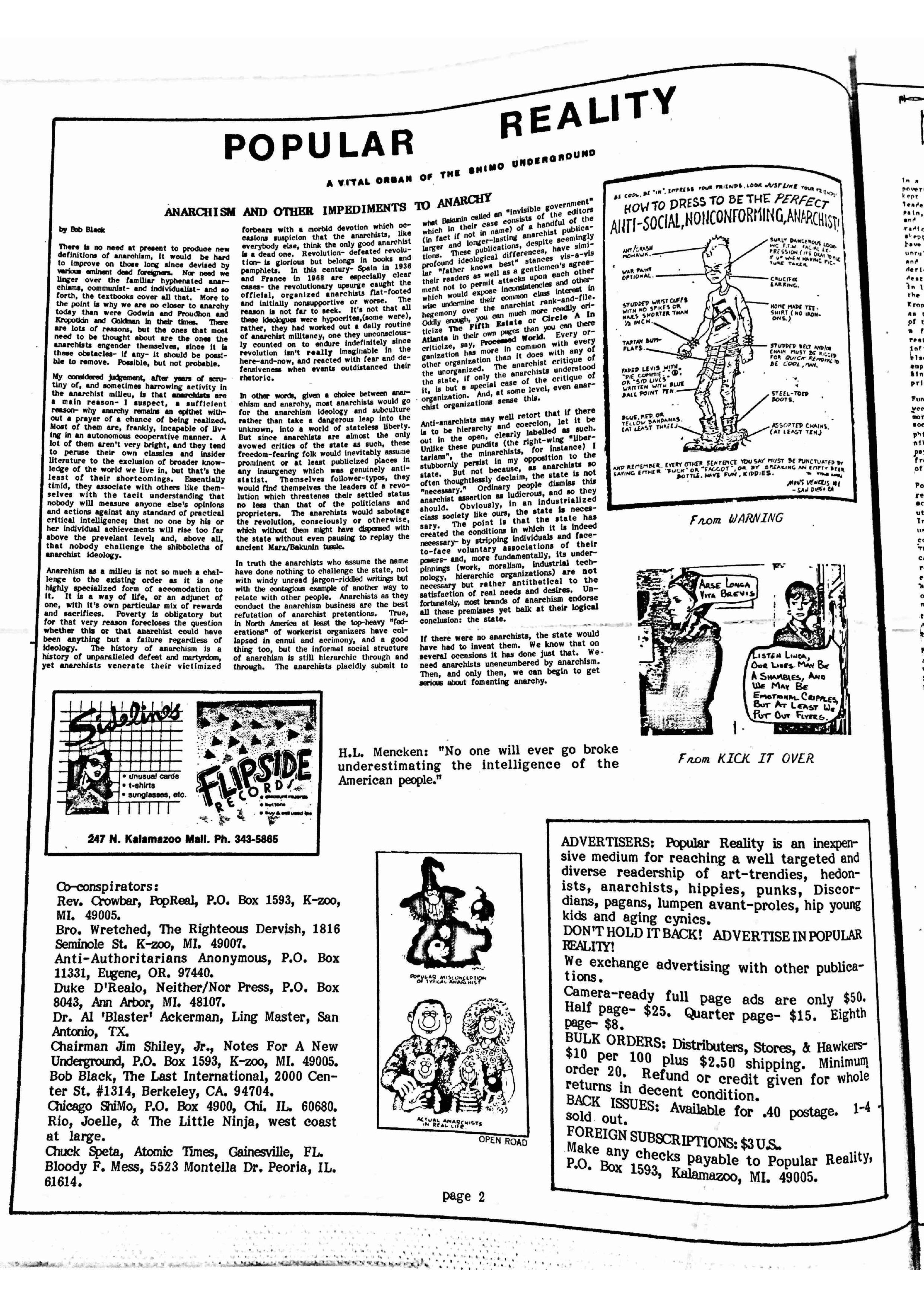

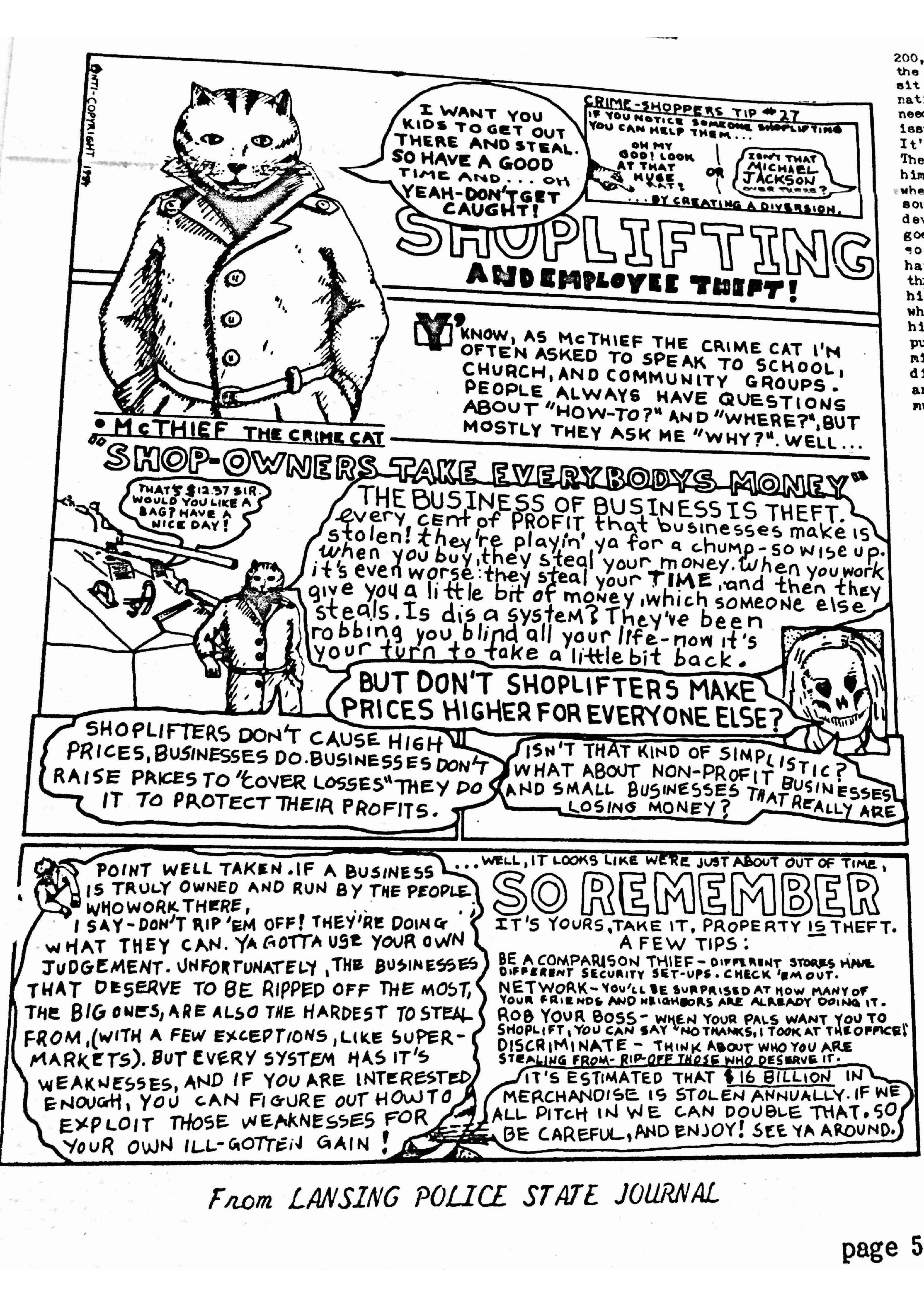

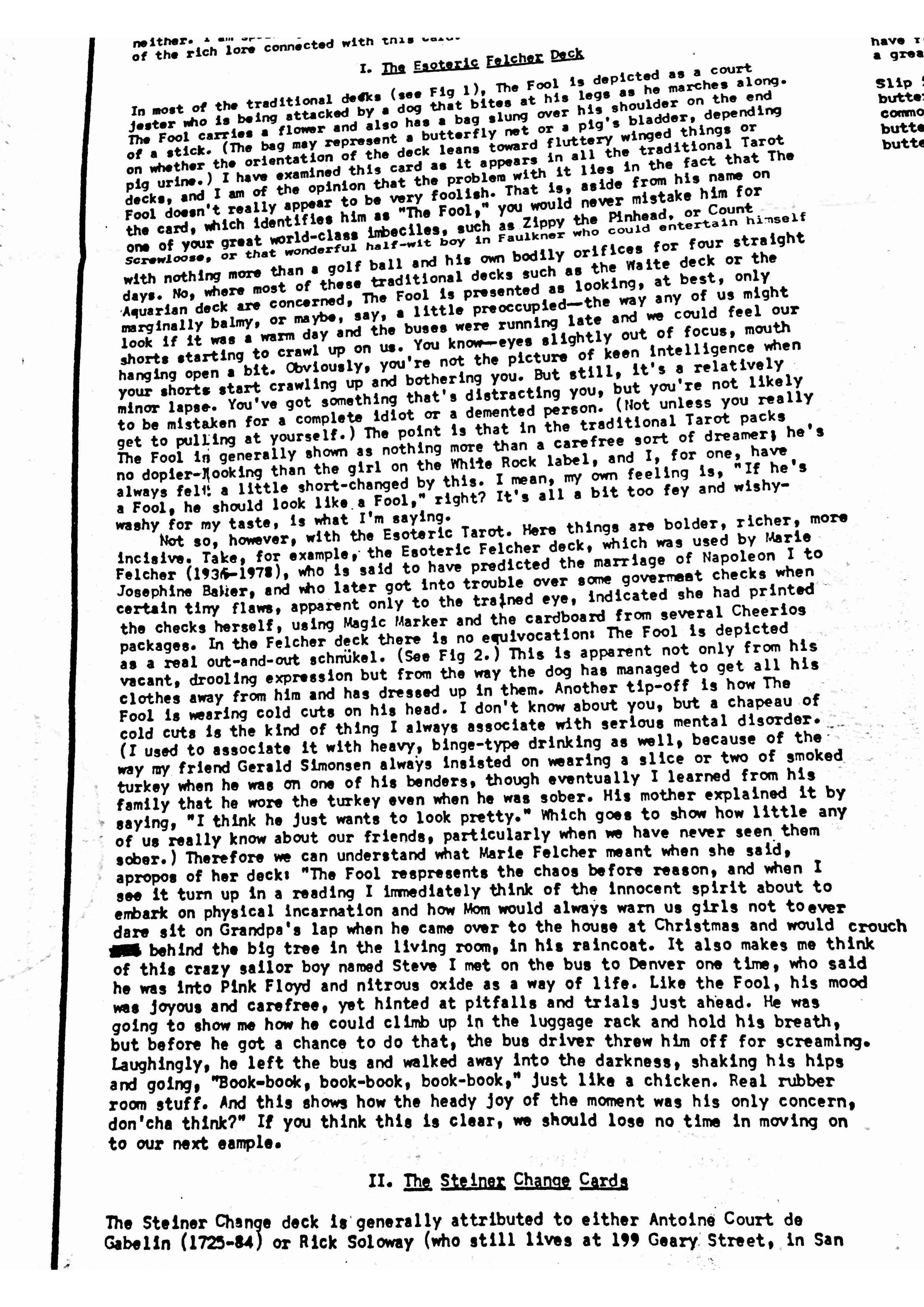

Guided by a devout opposition to intellectual conformity, Crowbar’s Popular Reality transgressed the subcultural boundaries that divided the fanzine culture into insular micro-scene. Proudly declared itself the “lunatic fringe” of Western civilization, the community of militants, or “marginals” that developed within the pages of Popular Reality included an array of unorthodox anarchists, occultists, literateurs, and humorists. The most recognizable figures included Hakim Bey (who used Popular Reality as a platform for the psychedelic fatwas of his Association of Ontological Anarchy), John Zerzan (whose Anti-Authoritarians Anonymous laid the groundwork for the Situationist revival of the 1980s, not to mention the post-Situationist ideology of "neo-primitivism"), and Bob Black (the polemicist extraordinaire behind the postering outfit, The Last International). Another noteworthy contributor to this underground digest was the unsung literary genius and renegade podiatrist Blaster “Al” Ackerman, whose Rabelaisian narratives scouted out heretofore untrodden domains of weird ribaldry. His current obscurity is a testament to the pitiful state of American Arts & Letters. Despite the zine's repudiation of dogmatism of any sort, issues of Popular Reality featured the tagline “the journal of social nihilism.” Though the ideology of social nihilism is self-evidently "post-Left" (cf. Black, "Anarchy After Leftism"), its precise meaning deserves further elaboration. The marginals’ ideology was nihilist insofar as it rejected the prevailing social order in its totality. The depth of this dialectical negation was profound, insofar as it encompassed all ethical imperatives, moral suasion, political ideologies, gender politics, and religious dogmas. This school of thought went beyond mere negation, though. Following the dialectical method, social nihilism was social in that its partisans believed that negation, taken to its absolute limit, was the only solid foundation upon which utopian forms of sociality could be built. Social nihilism construed modern society as a distorted cognitive space, as an illusory “spectacle,” which conditioned humanity to accept the logic of domination as normal. The marginals contrasted this pernicious illusion with the limitless creative potential of the imagination, which they conceptualized as “anarchy” and “chaos.” Inspired by the feral dream of creative destruction, they rejected socialist revolution as a tired dream and thereupon attacked those who would organize the masses into revolutionary movements as demagogues. The zine scene of the 1980s and 90s was a hotbed of controversy, and Rev. Crowbar’s zine distinguished itself as an open forum for the most unpopular opinions. To be certain, the marginals milieu established their revolutionary program of social nihilism through polemical exchanges, constant feuding, and the occasional violent confrontations with their opponents in various radical subcultures. Much more should be said of the minority opinions that defined Popular Reality, however, I shall leave the inquiring reader to form their own catalogue. Before I conclude this brief introduction to the Popular Reality fanzine archive, a note on the scans themselves is in order. Even the casual reader will immediately notice that the original pages of the fanzine have been rendered into black and white. The newsprint on the original documents has faded significantly; therefore, the black and white format is preferable on account of the way in which the sharp color contrast makes the text more legible. To my great disappointment, there are still some instances when even this post-production adjustment has not rendered the text readable. For these cases, new master documents must be located and scanned (so please do not hesitate to reach out to me if you in fact have access to original copies of the zine). Additionally, there is significant room for improvement with respect to the quality of the scans. Here, I can only ask forgiveness; this archive is a labor of love, and as such, there was simply no budget for using anything but the most basic scanning technology. Despite all of this, it is my sincere hope that scholars, admirers, and causal readers alike will find a form of mental enrichment unmatched by anything on the net in the pages of this marvelous publication.In Popular Reality, readers of today are able to catch glimpses of a lost world of revolutionary agitation. As the letters printed in the zine’s classifieds section demonstrate, the militant front that coalesced in Rev. Crowbar’s zine spanned all of North America. Furthermore, the fact that this fanzine branded itself as the “vital organ” of the mysterious ShiMo Underground did not dissuade the allied factions of militant psychedelicism (such as the Discordians, SubGeniuses, and the Noble Moors of the Moorish Orthodox Church of America) from adopting the publication as their own. The cross-pollination of such colorful strains of militancy made Popular Reality an invaluable repository of modern-day revolutionary theorizing, radical humor, and ludic phantasy. Perhaps more important, contemporary readers will also see that such collaboration made the fanzine a hell of a lot of fun to read. In closing, I would like to thank Susan Poe/Rev. Crowbar for her support and encouragement in the digitization process, as well as Jason Rodgers, whose inexhaustible passion for this material was a constant source of inspiration. Popular Reality No.1

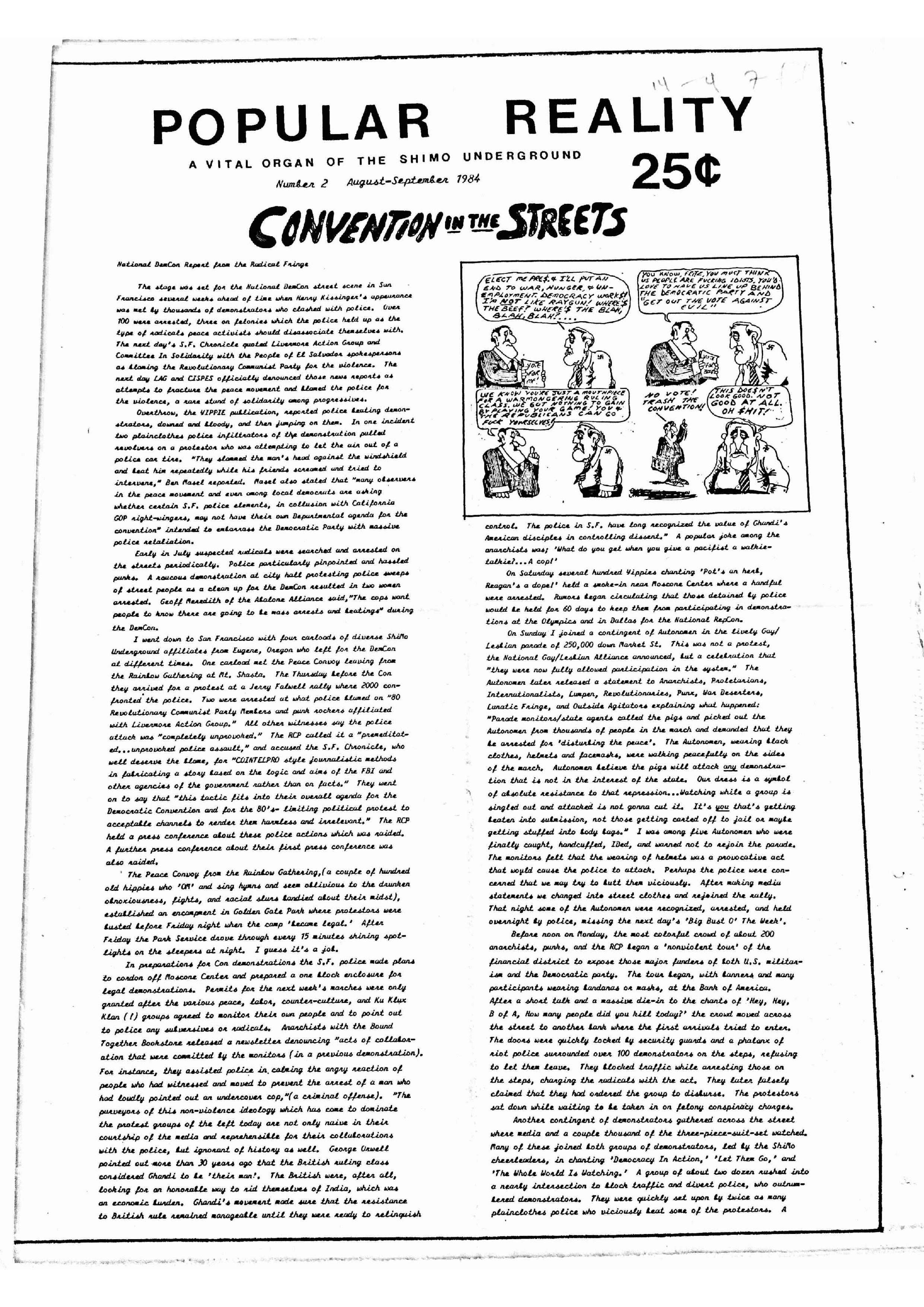

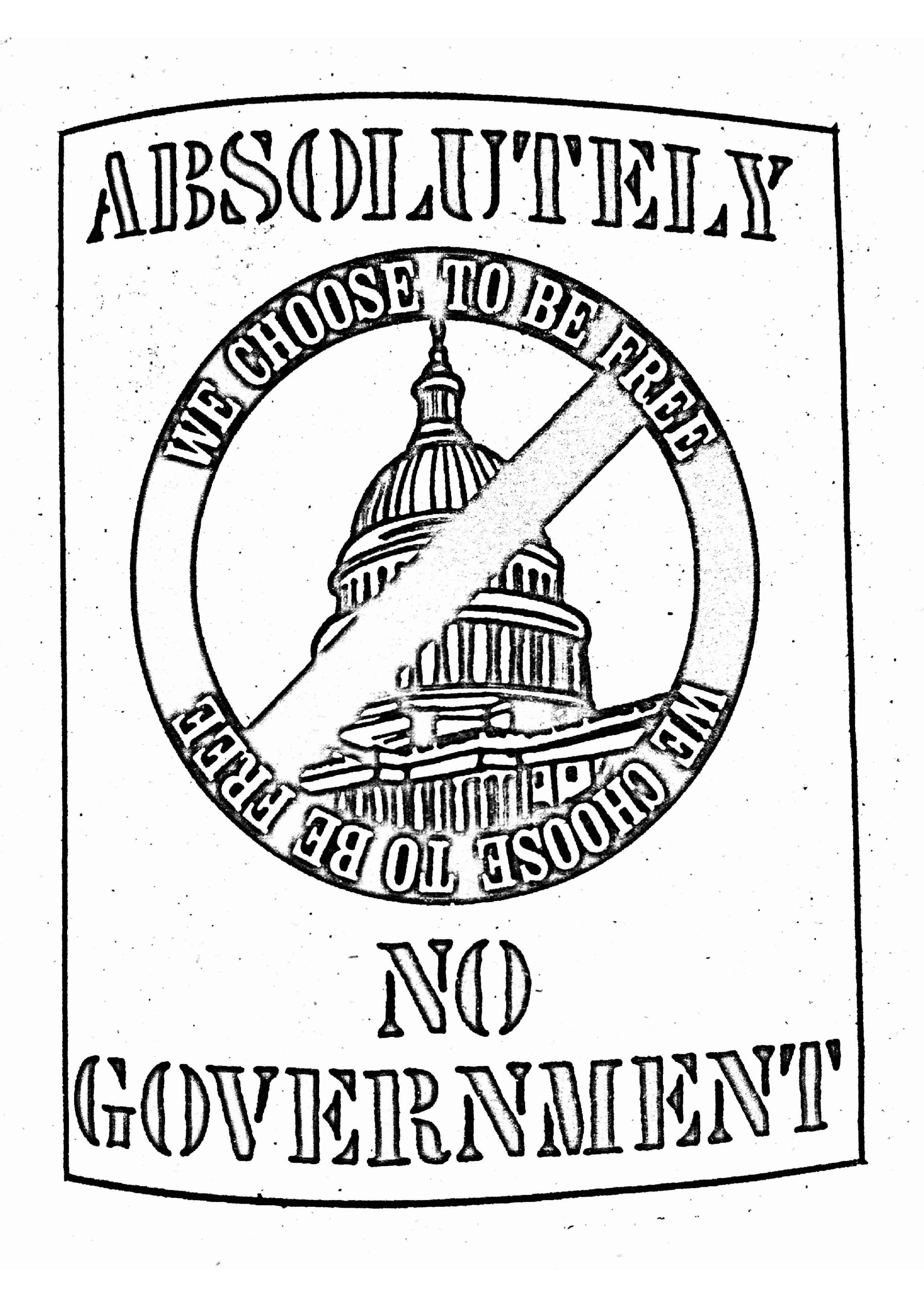

Popular Reality No.2

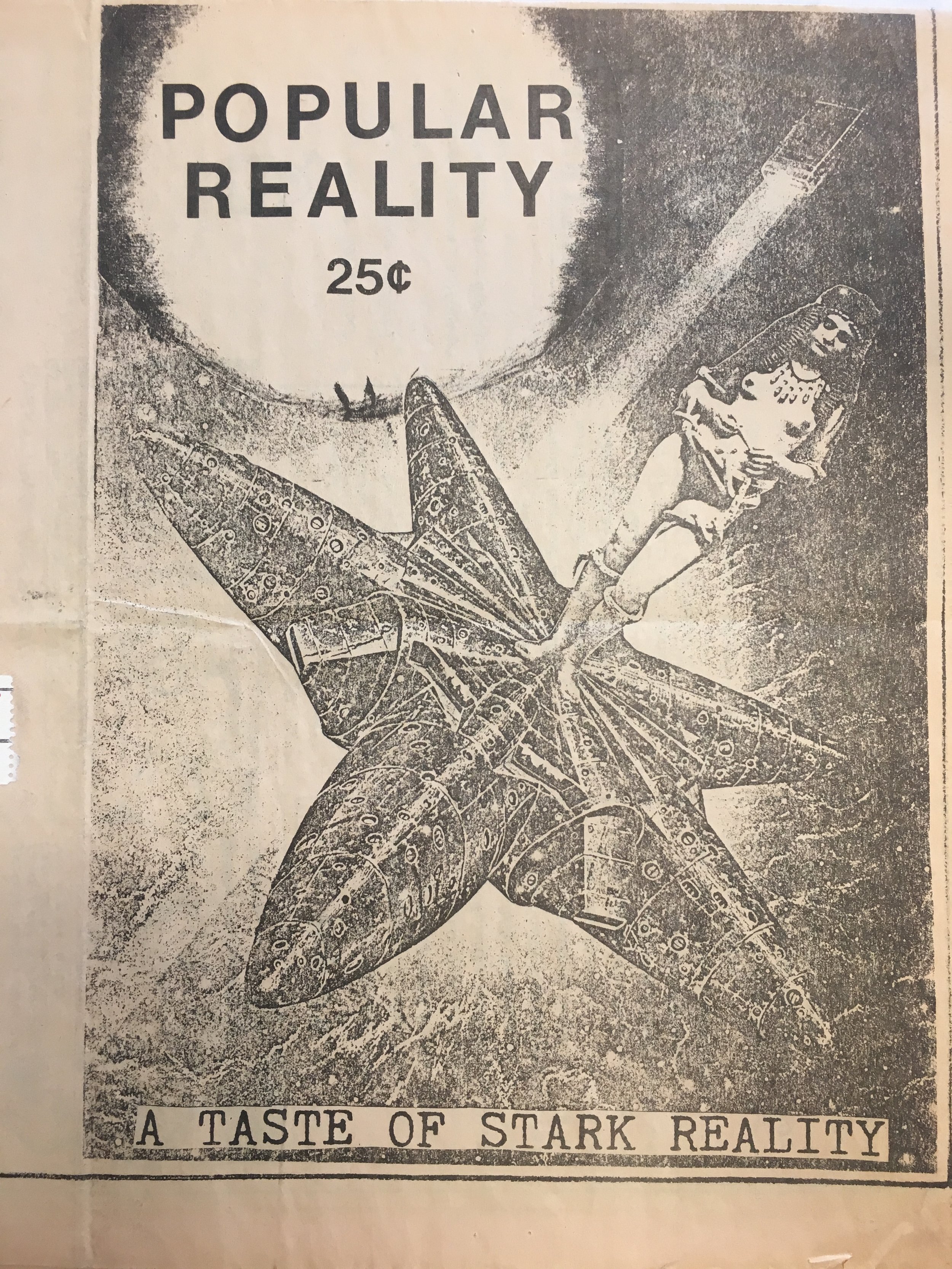

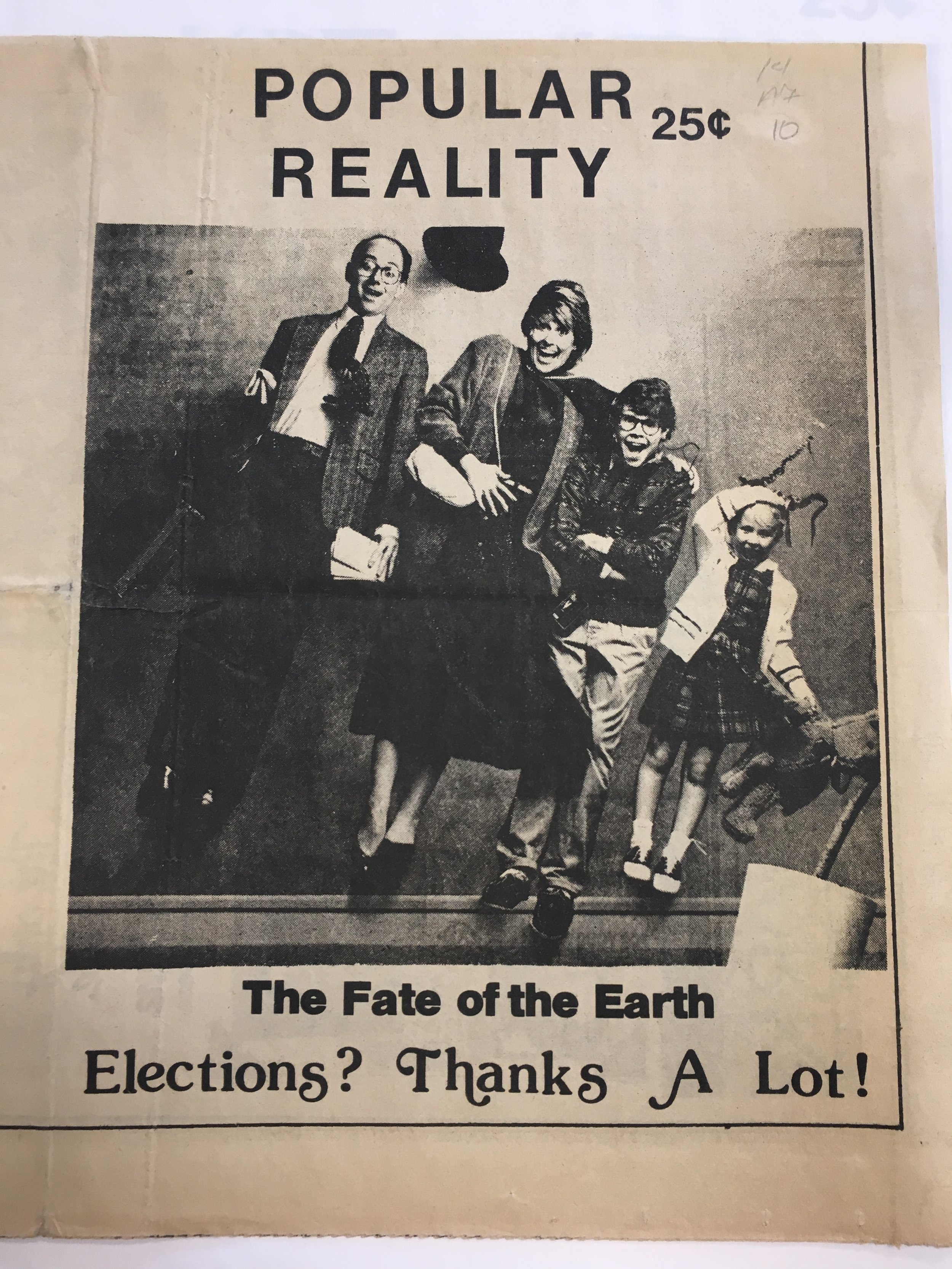

Popular Reality No.3

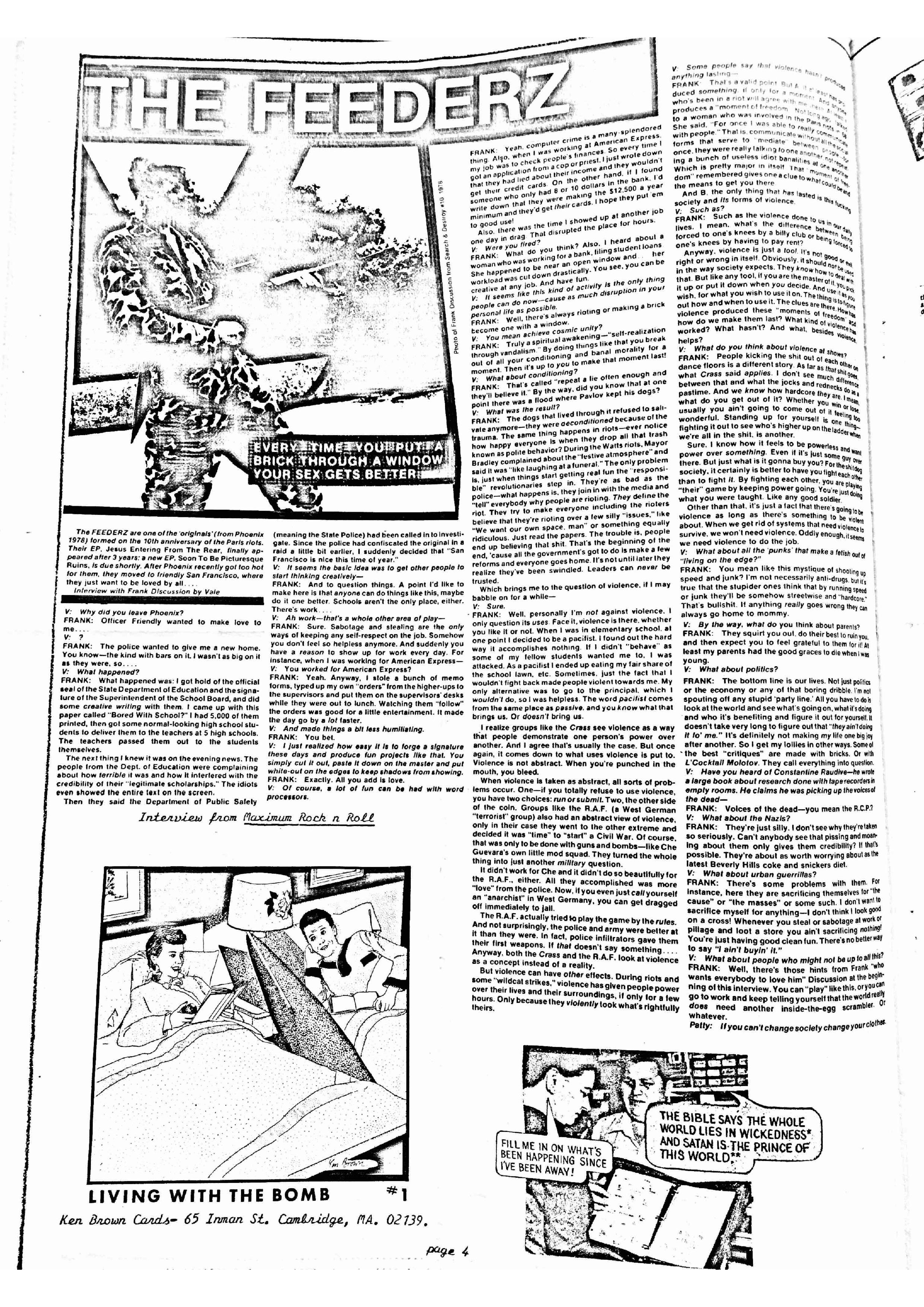

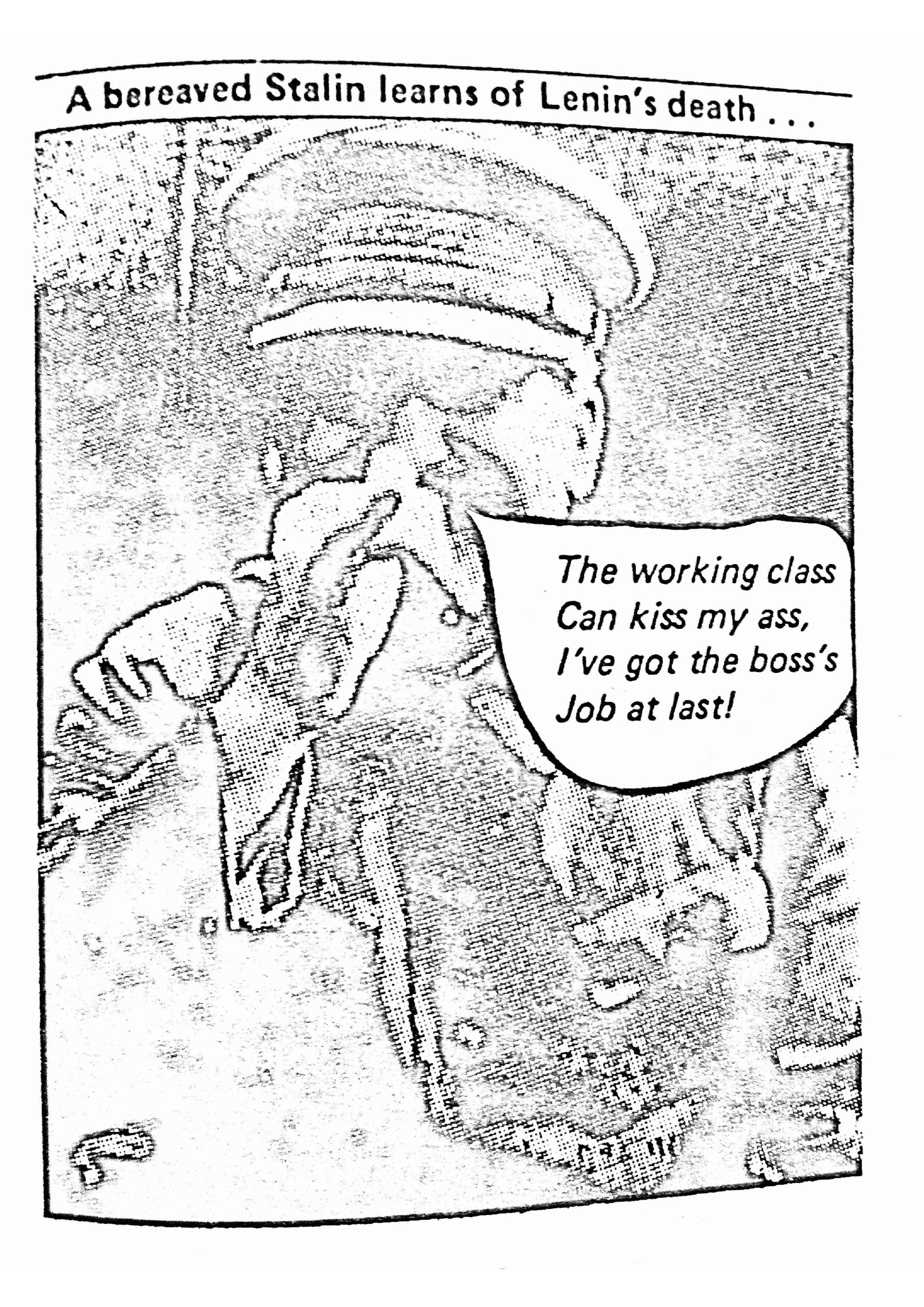

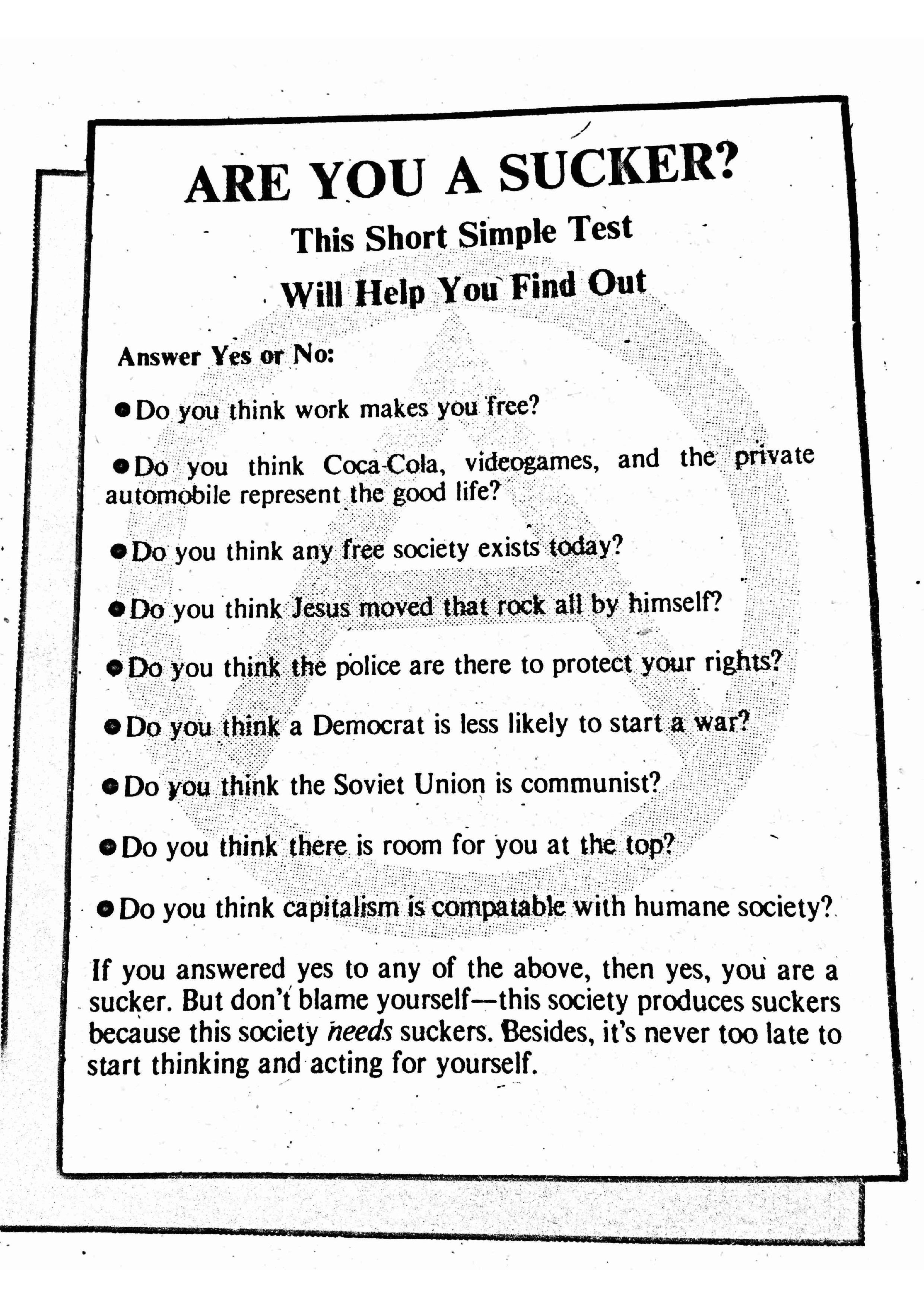

Popular Reality No.4

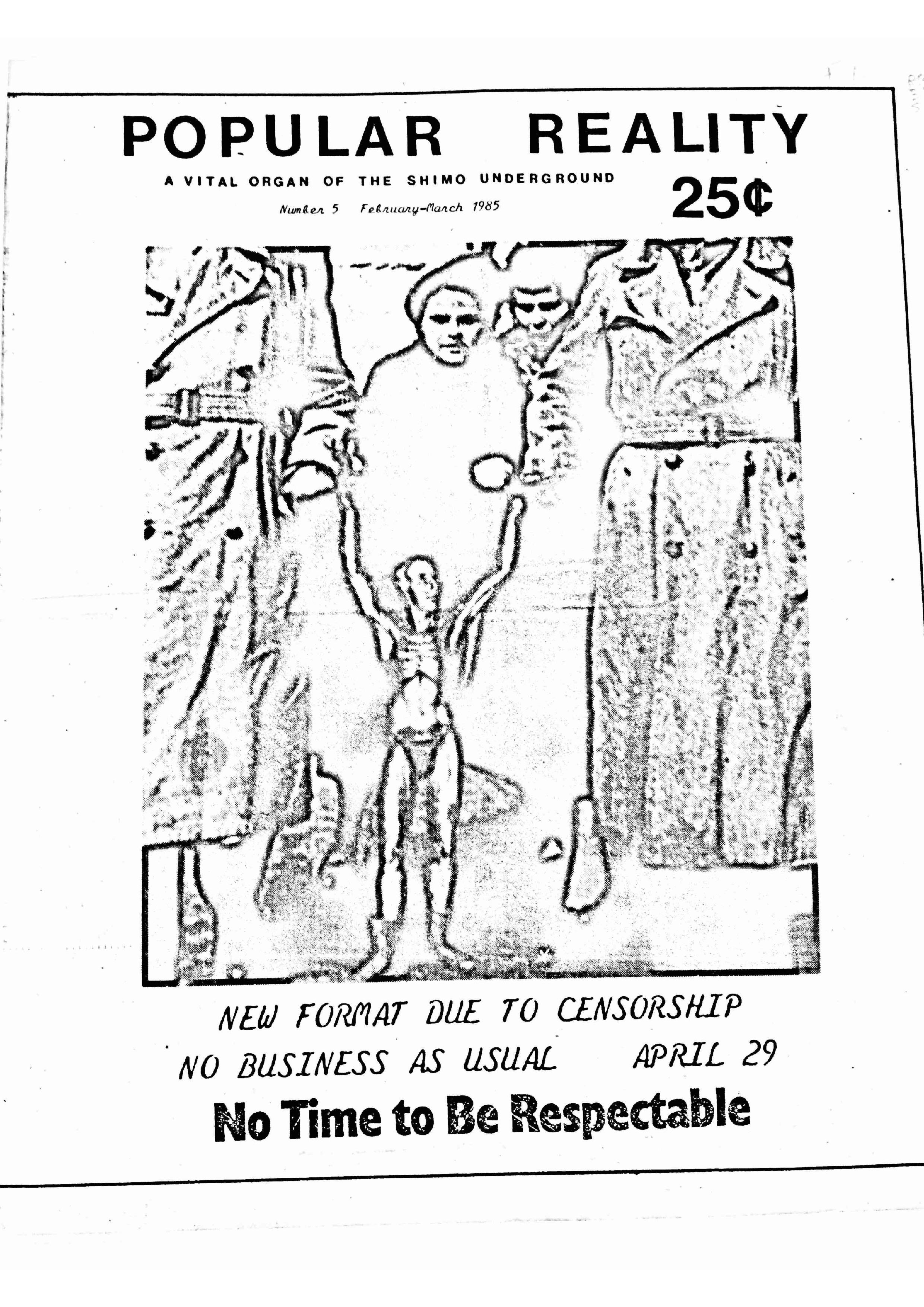

Popular Reality No.5

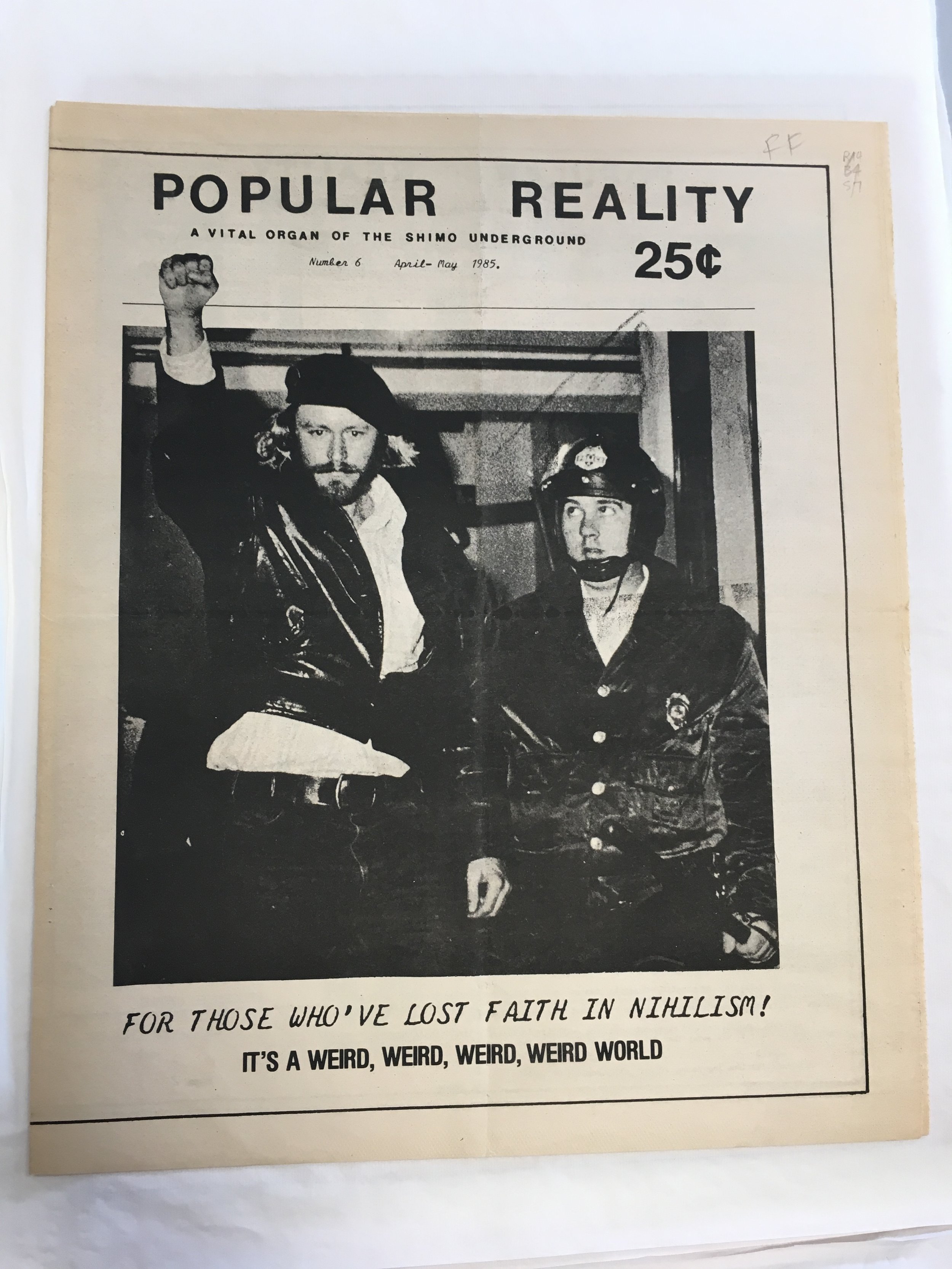

Popular Reality No.6

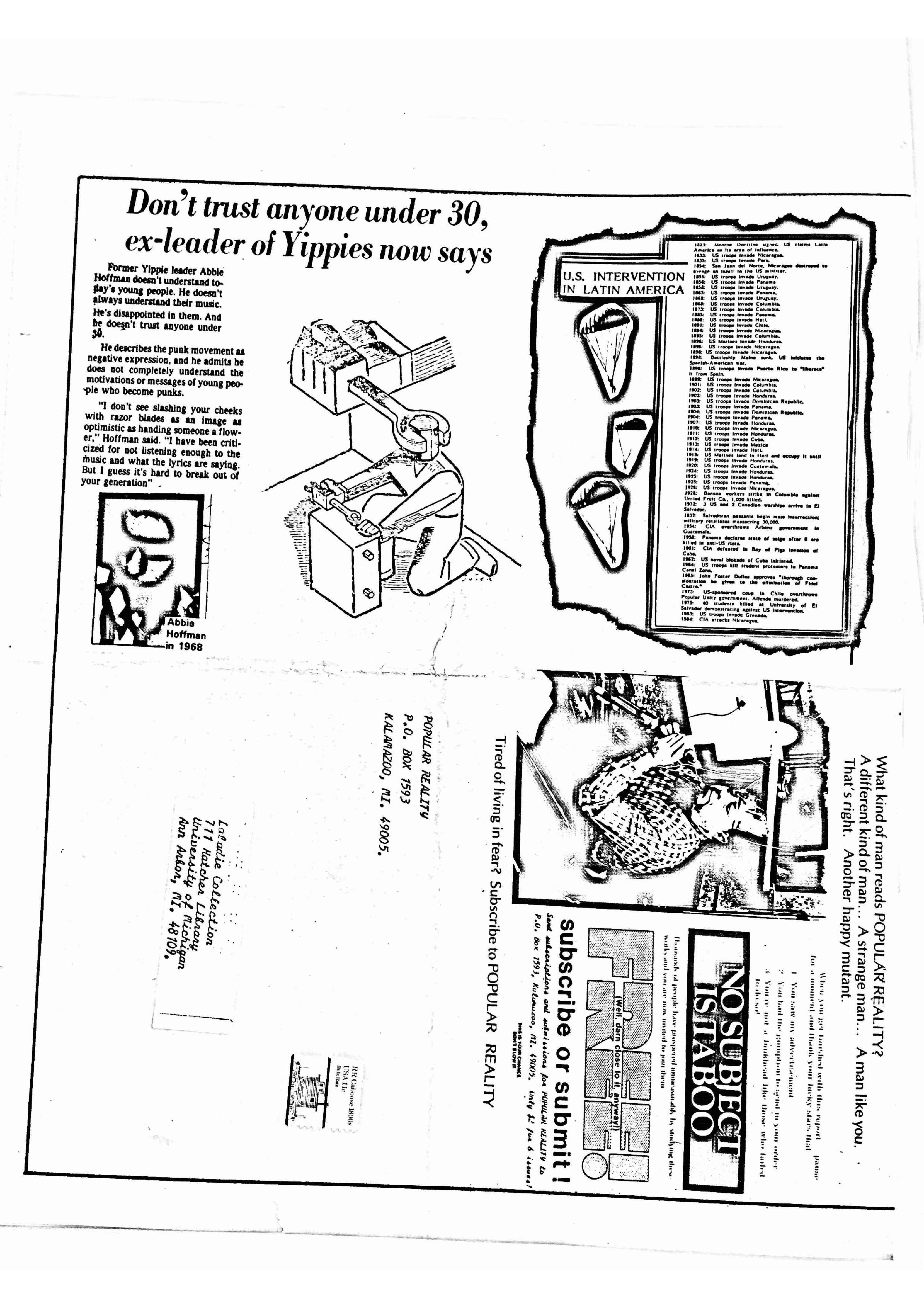

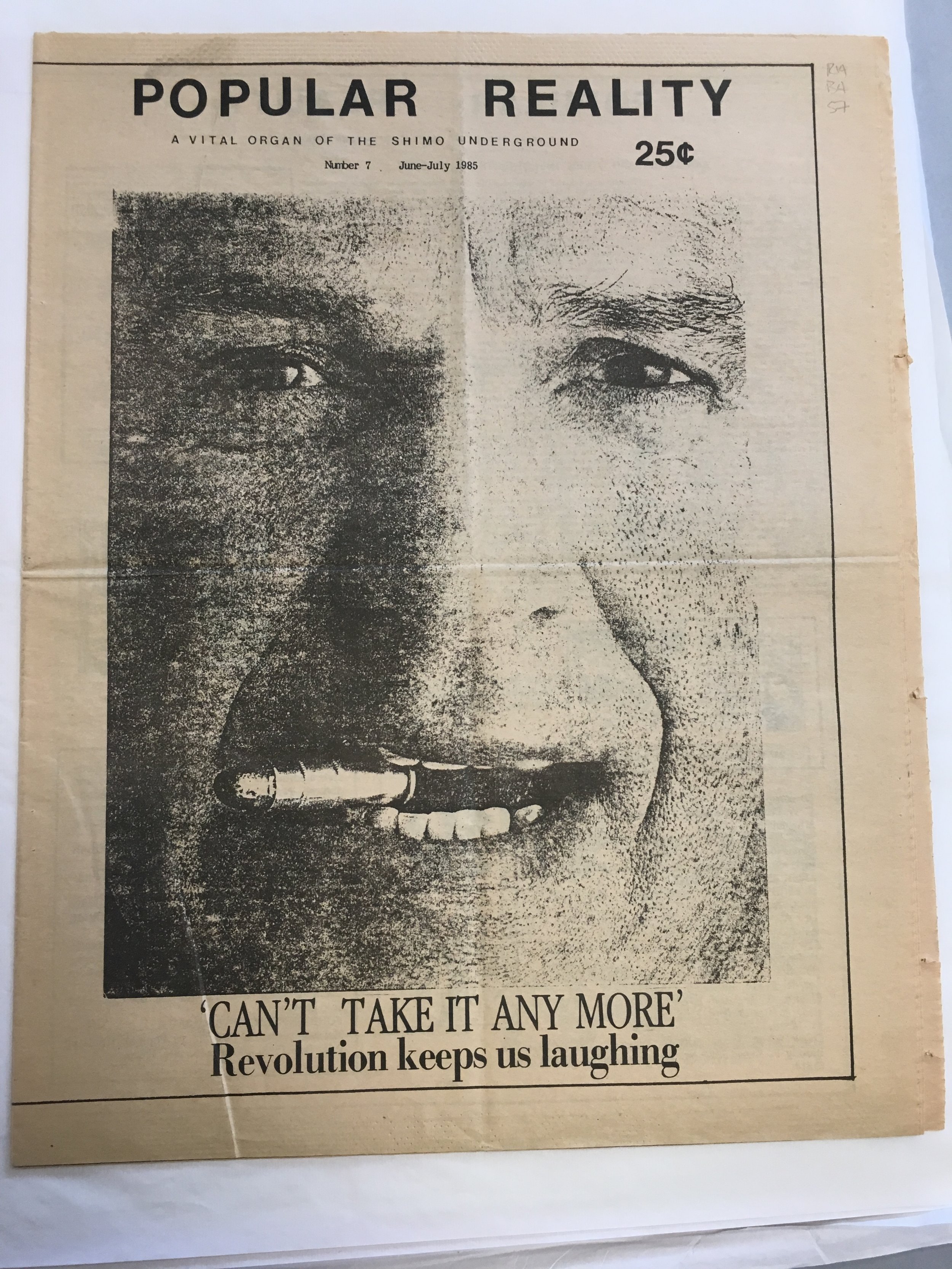

Popular Reality No.7

Popular Reality No.8

Popular Reality No.9

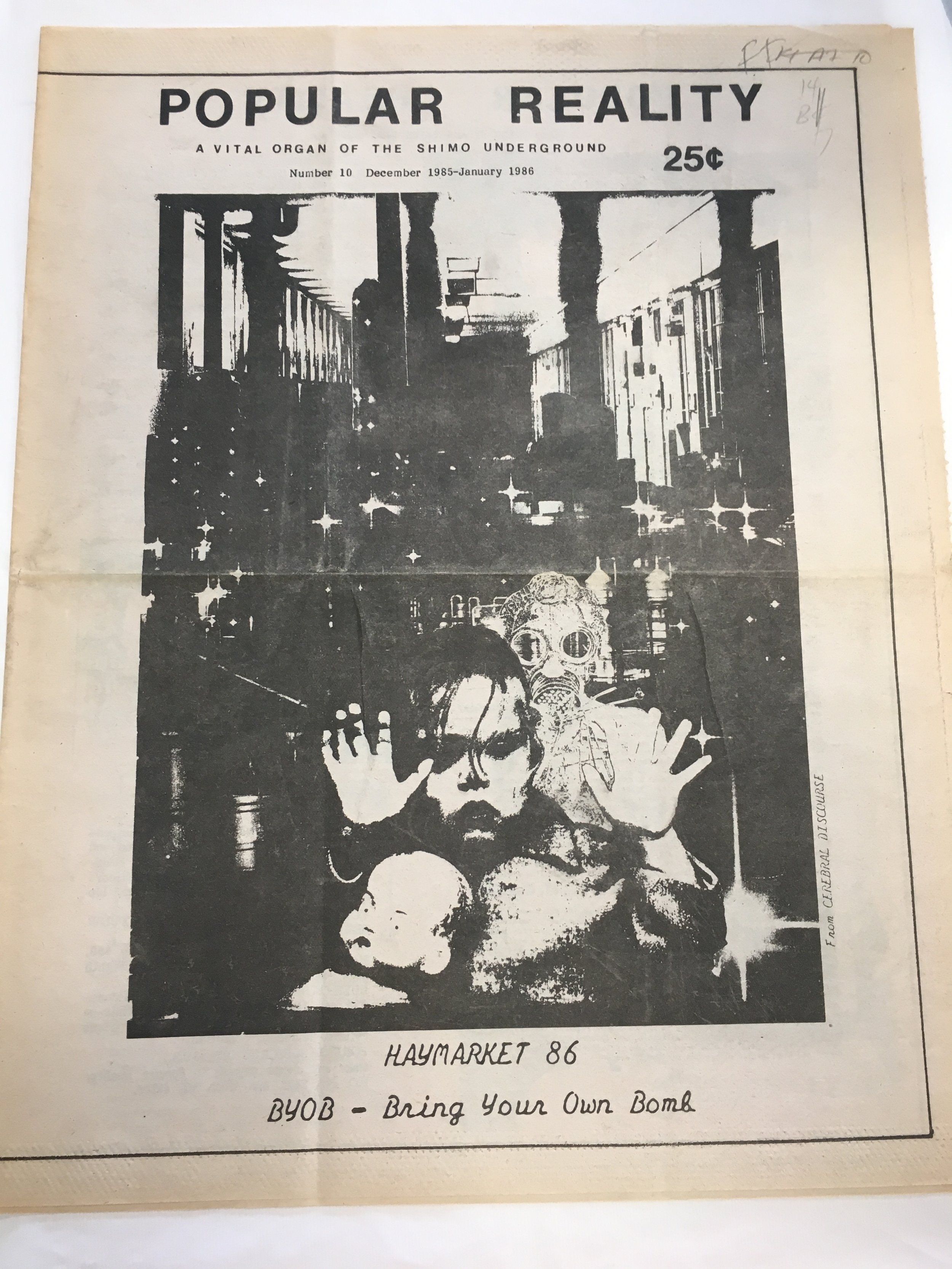

Popular Reality No.10

Popular Reality No.11